THE HOUSE ON THE BEACH

1

Once the decision was made, the practical organisation of it remained in spite of the numerous unknown factors it presented, not least of which was exercising a trade that was totally unknown to me and for which none of my previous experiences had prepared me. It was therefore decided that I advise Glenstal College that it would be impossible for me to continue for another year to exercise my functions there. The summer holidays were approaching and our paying guests and students in Dublin would soon be leaving us.

We therefore decided to send Rozenn and John to Brittany for the holidays, making it easier for us to prepare our new move. Marie-Madeleine would go to France later with Erwan and bring all three of them back at the beginning of September, as her French passport was still valid. It was necessary to let our respective families know about the new changes that were taking place in our lives and to make the necessary preparations. My parents were happy to welcome two of their grandchildren to Brittany in their house in Saint Lunaire where my father had retired and where they had plenty of room.

One of the young French ‘au pair’ girls who was returning to the continent agreed to take charge of our two eldest as far as Saint Malo, where my father was to meet them. She was a sensible girl who had already taken care of children and whose qualities we had been able to appraise during her stay in Dublin. I took Rozenn and Jean to Dun Laoghaire to catch the morning ferry and from there the young girl took charge of them. After crossing London in the afternoon, they were to catch the ferry from Southampton for Saint Malo that same evening, where my father was to welcome them the following morning. The young girl, on the other hand was going on to the town of Contentin. Their journey proceeded without mishap, though Jean was surprised that they were not stopping to visit the Queen in London. At the time, when airlines were only just beginning to operate, travel by plane was not common. The cost in any case was well beyond our means.

At the beginning of August, Marie-Madeleine also left with Erwan for Brittany . During her absence I prepared our final move from Dublin and the equipping of the small cottage that Samzun had rented for us, which was very close to The Pond. I was not able to take up my new functions before early August in any case. My father in Brittany was to settle the purchase, at a very reasonable rate, with Lucien Samzun of his share in the association that he and his brother had formed. The schools for the children were to start again in September and we were not moving to Cleggan before the end of August.

There was a small village school in Claddaghduff, three kilometres from The Pond, near the church. However, there was no school transport and the buildings were in a state of disrepair. There was only one teacher for all the classes and it was said that when the weather was good, he preferred to go fishing than to give classes.

We were afraid that the change would be too abrupt for Rozenn and Jean: the former was already nine years old and the latter eight. As for Erwan, he was still too young to go to school.f The Dominican sisters in Cabra, to the north of Dublin, the same teaching order as that of Muckross where the two eldest had been as day pupils, had a primary boarding school for young boys, close to the school for deaf-mutes and a boarding school or girls, which they also directed. We therefore decided to send Jean there until he was ready to start his secondary education. As for Rozenn, thanks to the recommendations of the Benedictines in Glenstal, we were able to send her to the Benedictine Abbey of Kylemore that had a boarding school for girls, about twenty kilometres from Cleggan. She would thus be much closer to us.

I gave notice of our departure by September from the house in Glenayr Road. ass I also had to purchase some beds and simple furniture for the cottage in Cleggan that did not even have the bare essentials. There were no wardrobes or cupboards. The large central room had a cement floor and a high ceiling covered with painted wooden planks: also a large fireplace containing a few tripods and a trammel hook with a heavy cast iron kettle hanging from it. A few primitive containers and cooking pots completed the cooking equipment. There was no water, gas, or electricity. Sparse lighting at night was provided by a few paraffin lamps hung on the wall. A kitchen cabinet held a small assortment of plates, cups and dishes. From the four corners of the large room were the entrances into four small rooms that could be used as bedrooms. In front of the window was a large table with two or three enamel basins where one could at least wash oneself and the dishes. Under the table were buckets of water that had to be filled from the lake a few hundred metres away on the other side of the road, below the house. There was a small porch opening out at the back with on one side a primitive toilet, a simple bucket under a unit made of polished planks with a hole in it. On the other side, there was an outside door that opened onto the fields and rocks. Between the two, a wooden bench on which buckets could also be stored. It was really the Wild West in all its primitiveness, though in a truly admirable setting. The windows at the front looked out onto the large lake of Aughrusbeg that was frequented by sea birds and wild swans. To the east, we faced onto the large expanse of sky with clouds rushing by and on the horizon the harmonious summits of the Twelve Bens, nearly always shrouded in a blue mist.

Yann Fouéré and Erwan in front of the cottage, with the lake in the background from where water had to be fetched in buckets.

Yann Fouéré and Erwan in front of the cottage, with the lake in the background from where water had to be fetched in buckets.

The cottage belonged to Michael Walsh who was to be our nearest neighbour. A bachelor and nearing his sixties, he had lived there himself until the death of his parents when he moved into the house nearby that had an upstairs and was much bigger. The house now belonged to him together with his brothers, both long since emigrated to America. As for his sister, she had married Richie King, the schoolmaster of the area. She lived with him and ten children in Claddaghduff, near the school and the church. Michael did not do much else other than seeing to the maintenance of the fencing around his land and the milking of his cows. In winter he also made his lobster pots, as he fished for lobsters in the summer, thanks to the currach he owned. He had been for many years a regular client at The Pond. His currach was moored on the little beach opposite it. The rent he asked us to pay was very modest: ten shillings per week, a third of the rent we had paid for the basement in Bray during the winter season. In addition, every morning free of charge, he would provide us with half a bucket of milk, still warm from milking his cows. There was far too much of it for himself alone in winter and, at the time, milk was not sold. It was only to be found in some shops in Clifden. One had to make arrangements with a farmer to obtain it. It was only much later that dairies were developed and equipped with modern methods of preserving.

Always wearing rubber boots and with a cap on his head, Michael had a permanent thin black line around his lips. He was constantly chewing tobacco, sometimes tucking the damp tobacco into the fold of his cap until he needed it again. This brought back memories of my childhood: a number of elderly people in Callac did likewise. Michael would also spit out a black juice that would land some distance away. He confided to me one day that he felt less at ease in the big house than in the cottage that we occupied.

“The fireplace is much larger here than over there,” he pointed out to me. “I could spit into the ashes much better.”

Our appreciation of comfort is, of course, completely relative. The milk he brought us every morning after the milking often contained bits of straw and cows’ hairs. We always strained it before boiling it. He noticed this and was quite annoyed.

“The milk from my cows is the cleanest milk you can find in the whole region.”

I explained to him that I was fond of the boiled cream that remains on top of the milk after it has cooled down. However, this did not seem to convince him. He was not a demanding landlord and we got on well with him during our stay there.

In order to complete the very inadequate furniture, Samzun had given me a cherry wood wardrobe that had been brought over from Haute-Bretagne. He had transported it over in his boat before the war with some other furniture that had been stored in Cleggan since then. We also inherited a double bed with a good woollen mattress that had not absorbed too much of the damp. We were thus able to hang our clothes and to sleep. Otherwise we had accumulated enough sheets and blankets from our previous abodes. I had three metal beds sent down from Dublin by train, to put in one of the rooms for the children. I kept back the three horsehair mattresses that I had bought at the same time. I was to load these with the rest of our possessions on the lorry that was to come in September to collect us in Dublin and take us to Aughrusbeg. In a secondhand shop, I also found a chest of drawers for our room, where we could put our personal clothing, and a small kitchen sideboard. I fixed up one of the small rooms into a kind of study with a couch bed that could be used as a spare bed. However, the room was so small that I was obliged to sit on the bed when I was writing. As for the few books and documents, they were to be arranged in the superimposed empty orange boxes that I had already used for a library during our stay in Bray. Our means did not permit any purchases other than those strictly necessary. The basic nature of this installation was certainly extreme, but it corresponded more or less with that of the other small cottages and dwellings scattered around the countryside in the area. I was surprised to learn that the local authorities based in Galway, more than one hundred kilometres away, gave modest subsidies for the building and renovation of houses, but made no provisions for toilets in any of them. Septic tanks were still completely unheard of except in Clifden. All around these houses were the fields, the bogs, the hollows between the rocks and the stables for those that were well off, all places where one could relieve oneself.

During my first visit to Cleggan on my own, when Marie-Madeleine and the children were in Brittany, Samzun had acquired an old secondhand Vauxhall that made my task much easier, allowing me to go to Clifden and even to Westport or Galway other than in the lorry

“A little van would be very useful,” he told me, “but they are too costly for our finances. Why not ask your friend Le Boulc’h in Dublin if he could fix one up for us at a modest price, by purchasing an old second-hand one.”

11

At the beginning of September I returned to Dublin to welcome back Marie-Madeleine and the children. Also, the last minute arrangements for the move had to be made. Alphonse, whom I had contacted according to Samzun’s request, was about to acquire an old C4 with a high ground clearance, and completely out of fashion, that could be transformed into a primitive van by removing the back seats and putting in a door instead of the boot.

“The work will be finished around the month of November ,” he told me, “as I can only work on it in my spare time. I do not want to take any money from you until it is done.”

I also had to visit some Irish families who were taking my paying guests and young ‘au pair’ girls. Nobody could believe that I was going to settle in Connemara, at the extreme West of the country: everyone’s eyes opened wide. Had I said I was going to the North Pole, they could not have been more surprised.

“You will never be able to live there,” I was told. “There is nothing there. Everyone is emigrating from there. You will never adapt to life there. If Cromwell banished all the Irish to the west of the Shannon, it was so that they would die of hunger there: which is in fact what happened, in their hundreds of thousands, a hundred years ago, during the Great Famine. Not for anything would I go and live there.”

Only those few Irish speakers who looked on Connemara as a holiday place, where their children were able to hear Irish spoken, seemed happy to see me settling there. Irish, however, was no longer spoken in Clifden, or in Cleggan, although the teaching at school was done through that language. One had to go further to the south, on the banks of Galway Bay, around Carna and Lettermore, in the Aran Islands and other neighbouring areas to hear it spoken. As for my Breton companions and friends that I was to see far less frequently because of the distance from Dublin, they knew well that making a living had to come first.

We were to leave the house in Glenayr Road during September, but before leaving we had to settle Jean into his new school in Cabra. Rozenn would come with us to Cleggan, before taking her to the Benedictines in Kylemore. Teaching there was also done through the medium of Irish. I waited for the arrival of Marie-Madeleine and the children, due on the morning of the 17th September at Westland Row station, after travelling across England. The train they were to take from Paris allowed them to arrive in Folkestone, then London in the afternoon, in time to catch the train for Holyhead and board that night the ferry for Dublin. Late that evening of the day preceding their arrival, Marie-Madeleine phoned me.

“I am still in Folkestone,” she told me. “I was held up on arrival and have therefore missed the train to London. I am not able to give you any details over the phone. But I will be delayed by twenty-four hours. I will spend the night in Folkestone and only take the train from London to Holyhead tomorrow night.”

I was perplexed, but realised that there must have been an incident on arrival with the British immigration services. It was therefore only on the morning of the 18th September at Westland Row station that I was able to welcome my wife and children, tired and hungry after a forty-eight hour journey. They soon fell asleep after a good breakfast at home on arrival. In fact, Marie-Madeleine had been practically arrested on disembarking from the boat at Folkestone. She had been separated from her children and subjected to a long interrogation at the border police station. My name, Fouéré, which was also the one on hers and on the children’s passports, had been entered in the big book at the time of my expulsion of those prohibited from entering Great Britain: as was also the name that was at the time on my old true-false passport.

I did not know it then, but found out later, that British immigration officers are the most disagreeable race of civil servants and bureaucrats in Europe. They assume powers of interrogation and arrest that they do not have. They always cover these up with formal legalities. It seems that as far as they are concerned, supported apparently by the services for the control of foreigners at the Home Office, the old Colonial prejudices against foreigners always start at Calais. Still to this day, as I write, they use the concern against international terrorism as a pretext to maintain their controls and their interrogations. This at a time when the States in the European Community, in spite of suffering from the same problems, have moved towards complete abolition of bothersome border controls, in order to ensure freedom of movement for people.

Marie-Madeleine’s interrogators, though obliged to admit that her papers were perfectly in order, were determined to make her say that she was coming to join me, which was correct, but also that I was in hiding somewhere, illegally, in Great Britain, at an address they absolutely wanted to know. Numerous phone calls were exchanged with a number of services.

“But I keep telling you repeatedly that my husband is in Ireland and that is where I am going to join him,” she kept on saying, showing her travel tickets.

The whole thing went on for several hours, during which time some policemen had to play the role of nannies. This delay prevented her from catching the train she had to take in order to catch her connections. In the face of her entreaties, they eventually released her and found a room for her and the children in one of the Bed and Breakfast places in town, so that they could spend the night there. She even had to pay for it, in spite of the fact that she had barely enough money to cover their meals and other small expenses on the journey.

Straight away the following morning, in possession of all the facts of these events, I lodged an official protest by mail to the Home Office, complaining about the behaviour of their civil servants and requesting a refund of the extra costs incurred by the delay they had caused. However, all I ever received were evasive answers in polite terms. On principle, a British civil servant, whoever he is and whatever his rank, can never make a mistake. He takes it for granted that the whole world must obey him. This was the case again recently during disputes between British services and Irish services, which regularly occur, in matters relating to extradition and control, in spite of the cordial relations that are maintained between the two governments and the official treaties linking them together on this point.

A few days later, our preparations, our trunks and our packing finished, and after taking Jean to his new school, we set off on the road to Cleggan. The little lorry from Samzun’s business, of which I was now a partner, had come to collect us. We piled on our trunks, our mattresses and our three pieces of furniture. A tarpaulin covered the lot. I kept a little space at the back where I settled down with Rozenn, whilst Marie-Madeleine and Erwan settled in front with John O’Toole who was driving. It looked very much like the vehicles used by the French, in their tens of thousands on the roads, during their exodus from the advancing German army and the occupation of Paris in June 1940. But the road we were taking was certainly not as crowded.

The journey lasted practically the whole day, though only three hundred kilometres separates Dublin from Cleggan. The roads were winding and their quality deteriorated as we drew closer to our destination. We quickly settled into Michael Walsh’s primitive cottage: not without Rozenn, already a big girl of nine years old, expressing surprise, though not wanting to really say so, at the poverty and basic nature of the decor. But she already knew that it was out of sheer necessity.

Two days after our arrival, we drove Rozenn in the secondhand car that Marcel Samzun had bought, to Kylemore, her new school. It was about twenty kilometres from Cleggan, along narrow picturesque roads that followed the meanderings of the bay, the lakes and the valleys.

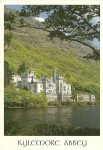

The Benedictine Abbey of Kylemore is situated in a majestic site, at the foot of the mountain, on the shores of a calm lake that is overlooked by the neo-gothic styled terrace of the castle. In the spring, clumps of rhododendrons and in the summer hedges of fuchsia surround it for several kilometres, clinging to the slopes, along pathways and the road that runs through the park, their enormous mauve, bright red or purple patches adorning and framing the whole area. Mitchell Henry, son of a spinner from Manchester who had made a considerable fortune manufacturing fabrics and textiles, built the castle in the middle of the 19th century. England was then at the peak of its industrial activity. Built of freestone, surmounted by towers, turrets and parapets that make it look like one of Blue-beard’s castles, the overall effect is rather unreal in this wild and grandiose scenery of lakes and mountains. The main building has long arched or ogive styled windows. Half Renaissance and half modern, it borrows from the Tudor and Jacobian style of numerous British public buildings of that time. Because of this it appears to be more modern than Glenstal castle, even though they were both built around the same time.

Mitchell Henry had spared nothing to make the castle into a prestigious dwelling. He had even gone as far as diverting, at his expense, the main road linking Clifden to Leenane and Westport, so that it would run on the far side of the calm lake, on the shores of which the castle is built, thus making it more isolated ; although he could hardly have been bothered by traffic in those days. He had also planted some rare species of shrubs and trees mixed in with oak, ash and indigenous holly in the park and the estate, which extended to approximately two thousand hectares surrounding the castle. It was a magnificent secondary residence for Mitchell Henry, a doctor in Manchester, who later became a deputy of the House of Commons, elected by Galway County. The building of the castle, the school and agricultural buildings, the catchments of water and creating his personal fire brigade had been a blessing for the country, coming as it did just after the Great Famine when money and work were scarce. In the Chamber of Commons, though he refused to get involved with the unrest of the Land League, Henry was in favour of Home Rule for Ireland. He never missed an opportunity to draw the British government’s attention to the critical situation and the needs of this backwater of the empire they represented. Unlike some other landowners at the time, he was not demanding when it came to the payment of farm rents.

Unfortunately, Mitchell Henry lost his wife in Egypt in 1874 during a visit there, shortly after the castle was completed. He had a chapel, modelled on Norwich cathedral, built in an isolated spot in the park, which the nuns still call the ‘Gothic’ church, as a burial place for her. It contains the remains of the Henry family. Mass is only said there on very rare occasions as a chapel was installed in one of the large rooms of the castle. Deeply affected by the death of his wife, Mitchell Henry gradually came less frequently to Kylemore. Because of the agrarian reform that obliged the large estates to parcel out their land towards the end of the century, he decided to sell the castle and the estate in 1902, apart from a small portion of it that was still occupied by his daughter when we arrived in Connemara.

The Duke of Manchester, who bought the castle and the estate, radically changed the interior of the large dwelling. He was partly responsible for the large monumental hall of Jacobian style leading to the large staircase to the upper floors, and to the dining room and large reception rooms all with precious parquet floors. However, he went bankrupt at the end of the First World War and had to put the castle up for sale in 1920. But the era of large landowners in Ireland was over. The Benedictine nuns managed to purchase it and part of the estate thanks to the generous help they received. They have since associated the name Kylemore with the Abbey.

The obtaining of Kylemore marked the return to Ireland of the Irish Benedictines. They had been chased from their country by the English anti-catholic penal laws of the 17th and 18th centuries. They had settled on the continent in Ypres, where they managed to survive, in spite of the anti-religious persecutions of the French Revolution. They had to flee from their convent, however, when it was burnt down and destroyed during the violent fighting that took place in Ypres at the beginning of the First World War. The Irische Damen, as the locals called them, had therefore contemplated a return to a new Ireland, where many of them came from originally. They had taken with them their relics and the flag that had been placed in their care at the beginning of the 18th century by Lord Clare, who was then commander of the Irish Brigade fighting with the King of France’s army. This flag that was held in trust by them was the one that the Irish Brigade had captured from the Duke of Marlborough’s English troops during the Battle of Remillies in 1706.

The Benedictine nuns had preserved the remains of these ancient splendours in the castle of Kylemore: they also cultivated the farm on the estate. They had been settled in Kylemore for over a quarter of a century.

When I brought Rozenn there to do her secondary schooling, there were still a certain number of nuns with Belgian citizenship. The Abbess, Dame Placid, was one of them. Dame Bernard, the principal of the school, was on the other hand a fervent Irish nationalist. My situation of political exile was the best recommendation, as far as she was concerned. Having been in Ypres, she spoke perfect French. Through her influence probably, and also because special subsidies were allocated by the State to secondary colleges that taught through the medium of Irish, the majority of subjects were taught there through Irish. This did not seem to bother Rozenn too much, having attained a certain flexibility in Wales already, from jointly speaking Welsh, English and French, our home language. Nearly ten years later when I wanted her to do an extra year in the final year at the Lycée de Nantes, she had to present her secondary school diploma, equivalent to our baccalaureate. This document, written entirely in Irish, astonished her professors and the French academic authorities there. A translation into French had to be done. English, German or Spanish were acceptable but that anyone would use Irish, though it is a language that is a cousin of Breton, was beyond their comprehension. French civil servants, and those in the National Education are no exception, are all cast in the same mould: even when they believe they are being original, developing theories or ideas that they think are in fashion or are new, and even revolutionary, they are seldom able to escape from the shackles of Unitarian ideology that conditions and distorts their reasoning, without them even realising it.

111

Our new life gradually became organised. The little cottage took on a more stylish appearance with curtains at the windows, and also more modern with the little Calor gas cooker I had been able to obtain, together with two little armchairs I had bought in Galway and the pressure paraffin lamp that we carried around with us from room to room, according to our needs. We had even provided it with a lampshade. It was a big improvement on the primitive lighting provided by the ordinary paraffin lamps, candles and the little copper lamp that had come from the continent before the war in Old Samzun’s disparate luggage.

The latter made do with a small paraffin cooker with only one burner, the camping type. At night he used a freestanding paraffin lamp with a long glass that must have been one of the glories of some bourgeois salon at the beginning of the century. All these instruments had to be attended to frequently, watching closely the wicks, cutting and trimming to stop them from smoking and burning away. They required constant care to maintain a good light and atmosphere. The turf fire constantly maintained in the large fireplace, as turf never goes out if one takes the precaution at night to bury the embers in the ashes, was mostly used for heating and to boil water in the large heavy kettle that hung from the trammel or rested on a tripod. Most of the nearby cottages did all their cooking on it. It was even used for cooking the brown soda bread of unrefined flour, buttermilk and a little butter. The dough was put into a cast iron pot that rested directly on the embers with more embers covering the lid of the pot, thus making a type of primitive oven. The saying in the country was that a girl was fit for marriage once she had mastered the art of making this natural, primitive but delicious bread.

We also soon learnt that there were only two things in Connemara that one did not economise on: turf and potatoes. In general, the wealth and prodigality of the owner of a house was judged by the size and height of his stack of turf, neatly piled by his door. Thus I was advised from the beginning to hire a bog in the mountains. The bogs were parcels of moorland fields, from which only a few metres width could be cut every year. Their wealth and productivity was judged by the depth to which one could cut before reaching the rock. The blacker the pieces are the more heat they provide when burning, like coal in that respect. The turf had to be cut in the spring, after the heavy winter rains. A special spade was used; narrow, with a cutting edge on the side that allowed one to dig up relatively even sized rectilinear pieces. But that was not the end of it. The pieces then had to be spread out on the ground to dry and after this first drying they had to be raised to a vertical position, leaning on each other, forming small heaps, allowing the wind blowing through them to complete the drying. All of these steps were very time-consuming, before finally gathering the pieces of turf and transporting them home by cart or tractor. I hired a bog the following spring: I had it cut by one of the farmers nearby and during the summer, having borrowed a donkey and cart, Rozenn and Jean spent a good part of their holidays transporting the pieces of turf from the mountainside to the roadside, where our little lorry was able to collect them. The process was not an economical one: other than for those who could do everything themselves and had no other productive occupation.

A number of men from the cottages around Claddaghduff, Cleggan and Cushatrough, with some help from their children, were mainly occupied in springtime with making turf, before the arrival of the mild weather that would allow them to take their pots out to sea. They spent part of the winter making and repairing the pots. They were neither farmers nor fishermen but a bit of both. They also lived at the mercy of the winds and the seasons, in complete communion with nature and the elements. As a general rule they disliked hurrying: for them time was of no importance. Before even thinking of looking for lucrative work, they first needed to ensure that they had a good crop of potatoes and sufficient tons of turf, thus themselves producing basic food for the family and the means of cooking and heating. They lived mostly in a closed economy, consuming their crops, the milk from their cows, eggs and poultry from their chickens.

To get a better idea of the work involved for the turf, I climbed several times to the top of the hill, overlooking Fountain Hill, not far from the lake that provides water for the little village of Cleggan. The spring was magnificent and promising: the sun already warmed the bogs. Here and there, turf cutters appeared: most of them first started by sitting down on a rock, probably for a rest after the climb. Then it was time to enjoy a pipe or a chew of tobacco, after cutting a piece of the hard compressed tobacco they used. During the day they stopped for tea and sandwiches: how could one possibly enjoy the magnificent sunshine and light breeze if one spent all one’s time cutting the bog, throwing the clods of damp turf, soaked with blackish water, over the shoulder, in a regular, though certainly tiring movement. Turf cutters were usually paid daily. The length of the day, never too long, varied considerably however from one cutter to the next. How could one recognise the good one from the not so good, the conscientious and hard worker from the one who was not?

It was also possible to buy dried turf, ready to burn, by the cartload. However, there were large carts and not so large carts: a cart is a cart, just as a day is a day. The gospel story of the vineyard workers was definitely applied here: but there were not many first hour workers. The assessment of the volume was one thing but to try and measure the working time seemed completely incongruous. I eventually decided therefore to buy the turf by the cartload or tractor load. As the use of the latter expanded, an estimate of the volume became easier. I became practically an expert in making stacks of turf: it is important to place the pieces of turf in rows one on top of the other in such a way that the rain cannot penetrate into the stack, and yet leaving a little space for the wind to get through. It is in any case impossible to cover the stack of turf outside with a tarpaulin: right from the beginning of Autumn, the violent winds would have got the better of the tarpaulin, which, having flown off, would be lost forever.

At times another one of our difficulties was in obtaining even the most elementary commodities. There were a few small shops in Claddaghduff and in Cleggan. Old Mrs.O’Flaherty at the post office in Claddaghduff, sold bread, potatoes, flour and sugar, but it was over two kilometres from Aughrusbeg. A little closer, at just over a kilometre, on the border of Aughrusmore, was Owen O’Flaherty, who sold bread and petrol. Stephen King in Cleggan, as well as Oliver Coyne and Mathew O’Malley who both owned pubs by the harbour, also sold some tinned goods, butter, tins of condensed milk and other non perishable items. However, Cleggan was four kilometres away.

Only in Clifden could most things be found, twenty kilometres away from us, barely qualifying as a small business centre. This was where the closest petrol station was situated, also two or three hotels and guesthouses, a chemist, a bank, the main post office, a small hospital, a few drapers, shoe shops, grocers and butchers. The local police station and the remains of an old prison, long since closed down, were also to be found there. A small industry of Connemara tweed and wool blanket manufacturing was beginning to flourish. The Stanleys sold cloth, clothes, boots and fishing equipment. The Walshes had just set up a small bakery business and grocery. The Mannions, the Foyles, the Lavelles, the Joyces and the Kings shared the clientele from the surrounding countryside, composed in the winter of mostly farmers and the usual horse and cattle traders for the monthly fair.

All these people came to stock up and crowd the streets making it impossible to move around on fair days. These were held in the streets just as it was in Brittany in the old days, in Callac, as I remembered it from childhood. In the summer, in addition to the fairs, there were the tourists, travellers and passing traders. A daily bus service linked Clifden to Galway, having replaced the picturesque little narrow gauge train that used to link the two centres in the old days.

Clifden proudly bore the title of capital of Connemara, although no Irish was spoken there. When we first arrived however, it was far from being the prosperous little town it has since become. Half the houses in the main street were going to ruin open to the winds or with collapsed roofs. The small harbour at the bottom of the hill no longer had any activity. Yet there was electricity in Clifden, locally produced from a privately owned waterfall. Fresh produce however, vegetables, fruit, lettuce or cheese, were seldom to be found.

Nonetheless, it was necessary to go there at least once a week for the weekly supplies. The old second-hand Vauxhall was very useful in those early days. For as long as Samzun was with us, until early December of 1950, I would also take the Vauxhall to transport shellfish destined for the Paris market. A tiring overnight journey, arriving in Shannon in the early hours of morning to load the shellfish on the American transatlantic flight that made a refuelling stop on its way to the continent. It gave me the opportunity of doing some urgent necessary shopping in Galway on the way back. Later on, when the transport to Shannon became more frequent, we would give the driver a list of merchandise and various things to get for us in Galway, saving us special trips.

Health care was also a problem. We generally called on old Dr. Irwin, who lived in Ross, on the far side of Cleggan, further along the coast towards Moyard and Letterfrack. He was originally from there, but had long since retired from his practice. His brother was the Anglican minister of the church in Moyard, and another brother, ex-Colonel, lived nearby in Garrenbawn. Dr.Irwin had been to France with the British army in the First World War as a Doctor for the British expeditionary forces. Having returned home, he never refused to provide emergency assistance whenever neighbours sought his help, and generally never charged them. His kindness was well-known. Although his religion automatically classified him as one of the Anglo-Irish from that region, he still remained very popular amongst the locals. At the time of the uprising and civil war that bathed the country in blood in the early twenties, he attended without any discrimination to the rebels or the volunteers, from both camps, wounded during skirmishes and guerilla operations, maintaining absolute secrecy as to their movements.

One day, he had been attending to the wounded from a rebel commando at his house, when a patrol from the opposing camp, sent out in pursuit, arrived on the scene. He quickly helped the wounded out through the back door leading towards the mountain. He then opened the front door, and confronted the new arrivals.

“How are the boys and where are they?” asked the leader of the new arrivals.

He put on his most surprised look before replying.

“They are very well thank you, but they are not here, they are in college in England,” he added, referring to his sons.

“You know very well that we are not referring to those boys.”

“No, then I have no idea. But you may come in if you so wish, and

if you have need of my services.”

The former did not pursue the matter. Might he not one day also have need of a doctor!

There was a small general hospital in Clifden however, but with no surgical or blood transfusion facilities. For these it was necessary to go to Galway, nearly a hundred kilometres away. Doctor Casey had just taken on the hospital’s medical services and those of the surrounding region. An excellent practitioner, a competent and conscientious doctor, he soon became our medical consultant. He spared no effort in his devotion to his patients in general, and to people like us, in spite of the remoteness of where we lived, of the elements, the muddy bogs wet with rain, the wind and the storms.

In Clifden however, there was no dentist: there was one who came once every fortnight for consultations, but gave no dental treatment, simply doing extractions if necessary. Even then, he did not perform extractions on everyone. It was said that he refused to pull out the teeth of patients from Bofin or Shark, their jaws being too tough for any extraction without complications.

The closest dentist was in Galway or Westport. Westport was closer by about thirty kilometres. We therefore all became patients of Dr. Gill who lived in Westport, a small town in the next county, a good centre for supplies and business, generally cheaper than Galway. The town is situated at the far end of Clew Bay, renowned for its numerous islands and islets, “as many as there are days in the year”, was the saying, as it was also of the Golf du Morbihan in Brittany. The bay is sheltered from the open sea by Clare Island, site of Graine O Malley’s fortress, whose imposing outline and high cliffs we could just glimpse from our windows. To the south of the bay, dominating the ruins of Murrisk Abbey, a few kilometres from Westport, is the sacred mountain of Croagh Patrick, rising sharply above the sea and the islands, with its harsh conical silhouette. We could also catch a glimpse of it on clear days from our windows, navy blue, grey, or blue-grey depending on the light and the season: it was even possible with good binoculars to distinguish the small chapel erected on its summit in honour of the patron saint of Ireland.

Old Vauxhall with the cottage in the background. Marie-Madeleine, Rozenn and Jean in the foreground.

Old Vauxhall with the cottage in the background. Marie-Madeleine, Rozenn and Jean in the foreground.

It was virtually impossible, in our new place of abode, to manage without some means of transport. Public transport went no further than Clifden. There was no other way to get around than to arrange for a taxi or to walk. It was therefore essential that Marie-Madeline, and later the children, learn to drive. At that time in Ireland, there was no such a thing as a driving test. All that was needed to obtain a driving licence was to buy it every year or every three years, certifying on your honour that you were fit to drive a car without being a danger to others. I had thus been able, without any difficulty, to obtain a driving licence permitting me to drive all cars, including lorries. The only exceptions were buses. I made sure Marie Madeleine became familiar with driving the old Vauxhall, before obtaining her permit with a good conscience. Later on, I did the same for Rozenn, Jean and Erwan, as soon as they had reached sixteen: not without dents and scratches being inflicted on the bodywork, as well as damaged fenders and bumpers that sometimes had to be replaced. Some of the young workmen employed at The Pond equally gained their driving experience thanks to the small van belonging to the business.

Driving along the Connemara roads and tracks was not without some unforeseen difficulties. Communication routes belonged to the animals before belonging to humans. The sheep crossed over them, resting there at night to get away from the dampness of the fields. The cows, whose reactions were unpredictable, grazed unsupervised along the verges. The dogs in the neighbourhood had the habit of rushing out to bark at moving cars, trying to bite the tyres. Thus it was that one-day I ran over “Hitler”, Michael Walsh’s dog. I just had not seen him coming.

Besides, our cars were also something else; one could write a saga about them. We did not have the means to buy new ones, and had to be content with what we could find on the second-hand market. The steering of the Vauxhall went first, and soon after, the whole car gave up the ghost. Admittedly, with all our local comings and goings, plus the consignments to Shannon and the occasional collection of small loads of shellfish, our mileage was high. We replaced it with a C4 Citroën, high on the road, all the rage at the end of the twenties, which our friend Alphonse had somehow managed to transform into a van. Even in the West of Ireland it looked like an antique. At one of our stops on the road to Westport, the owners of the Halfway Inn asked us if we were part of the circus that had announced their coming tour of the region. It was a great help to us just as it was. We replaced it with a Terraplane, a large American car, which the nuns in Kylemore wanted to dispose of. It was very powerful but extremely noisy. The doors shook all over, so we had to secure them with string, and the exhaust pipe with wire. One day as we were driving along, the battery became detached and fell out, the car coming to a standstill. It was a good thing that our little vans were able to come to our rescue when necessary. It was only later when the business had expanded that I was able to buy a new Austin for our personal use only. After that it was a series of Wolseleys that I generally changed every 3 years. They were put to the test by the roads and tracks we had to use. Later on I was able to add to our only second-hand lorry a van that was easier to manage and was faster for the consignments to Shannon. However, it took us several years to reach that stage.

IV

When, at the end of November 1950, Marcel Samzun left for Brittany, leaving me alone for the first time to look after The Pond and manage the business, one of my first concerns was to undertake the building of a more comfortable house on the premises, larger and less primitive than the little cottage we were temporarily living in. The fishing was over and there was just some stock of lobsters and crayfish left to clear. The regular consignments we were sending to the Paris market for the agents, entrusted by Samzun with the sales, ensured a rapid clearance of this stock. From time to time there was in addition several hundred kilos to be sent by air to some Breton and Belgian fish wholesalers, who formed the regular clientèle of the business. The packing was generally done late in the evening or during the night. With the collecting and buying over, the workmen at The Pond could be employed for other tasks during the day. They were firstly employed for the extraction of pink granite stones from a nearby quarry owned by John Delappe, M.Samzun’s foreman since the nineteen thirties. At the end of each day, the lorry brought the load back to the premises. There had to be enough stone in place before starting on the building. The walls had to be thick to withstand the winds and the rain and I had no liking for the lighter buildings, of breezeblocks or concrete, which were certainly easier solutions. Also I did not want it to be a blot on the landscape. Already I had before me the hideous square cement block that served M.Samzun as both an office and living quarters when he was there. I therefore decided to incorporate this unsightly block into the proposed building. It later became our kitchen.

M.Samzun’s square cement blockhouse.

M.Samzun’s square cement blockhouse.

I did not have the means for an architect, and had to make do with what I had. I spent hours drawing up primitive plans, measuring and marking out as well as possible the site for the new house. I even decided to request advice from Mordrel, who had landed in Argentina and at first worked in an architect’s office. Himself an architect, he knew the tricks of the trade, the pitfalls to avoid and the mistakes not to make. His help was invaluable in setting out the final plan of the house, taking into account the limited surface area of the land I had to work on, and also the fact that I had to take special care to keep the sewerage waters away from The Pond. The building of a septic tank was therefore necessary. The only place we could put it was on the piece of land in front of the house, on the other side of the path going down to The Pond, which separated us from the beach by fifty metres. We first had to blow up a number of rocks that stuck out from the ground. Fortunately John, who had been involved in the building of the pond was a specialist in quarry work. However, the holes for the explosives had to be dug out by hand, with a sledgehammer and chisel. I also had to plan for the water supply, and therefore had to build a large cistern behind or under the house, to store the rainwater that would run down from the roof.

It was not until the beginning of the following spring that we were able to start digging the foundations of the house. We would buy the bags of cement either in Clifden or in Galway where they were cheaper. We generally collected the rough stones ourselves, plus the pebbles, gravel and sand that we needed from the neighbouring shorelines where the rocks and creeks were accessible. There were no regulations against it at the time, in that distant place: notwithstanding, none of our neighbours or workmen seemed to worry about that sort of thing.

I sometimes joined in the work, often interrupted and slowed down by the bad weather, wielding shovel and pick axe to reach the rock that would ensure a solid foundation: essential in this area battered by the winds where the unstable damp peat soil provides no guarantee of stability or solidity.

The 1951 fishing season was approaching, however. We now had to put the maintenance, cleaning and preparation of The Pond in the forefront, and the repair or making of the few floating wooden tanks we possessed. They were essential, as much for our work at The Pond as for the nearby fishing centres where our agents bought and stocked the shellfish for us, in Inish Bofin, InishTurk, Ballyconneely and Carna. It became necessary to employ a local mason in order to minimise the slowing down in the construction work of the house. The foundation work and laying of the first stones could be done by him with the help of a permanent assistant who could remain at his disposal and not be involved in the daily work of The Pond.

The following winter we were able to take up the extraction of the stones again. Nothing had prepared me for this sort of work, which was a combination of that of architect, land surveyor, developer and contractor. Neither our finances, always bled white during the buying season, nor the profits we could expect from the business allowed me to do otherwise. I had to do things myself with the limited possibilities and the means at our disposal and the credit we could obtain from local suppliers, in particular for wood, cement and timber frames, from the building materials firm of T’MacDonagh, with whom M.Samzun had had business dealings for over fifteen years.

The credit system was used to its maximum at the time, from firm to firm, business to business and shopkeeper to private individual. It was essential as, during the summer months when we did all our buying of shellfish, we quickly exhausted the modest credit afforded to us by the bank. Also it was not possible to transfer capital to Ireland from the continent. The only transfer facilities were between Ireland and Great Britain. We had to pay cash for our purchases from the fishermen: the slack winter season often left them also in debt. Apart from a few exceptions, we only paid our main suppliers once or twice a year, whenever the returns from our sales made it possible, generally during the winter, after the end of year festive season that marked the high point of sales for this type of business.

Marcel Samzun, who had been well known there for many years, had fortunately an excellent business reputation. People generally had far more confidence in him than in a local merchant. Nonetheless, we could not entertain any excessive expenses, nor even necessary ones; we had to constantly watch our budget and manage it carefully. Thus, through force of circumstances, our suppliers often acted as our bankers. It was said in those days that it was sometimes necessary to wait until the death of a debtor to be finally paid. The system was possible within a stable economy that had not yet been touched by inflation, depreciation in the value of money and loss of purchasing power. This was also still the case for the pound sterling, on a par with the Irish pound, when in the depths of the Irish countryside, shortly after the Second World War, I took my first steps in the business world and learnt a new trade.

The building of the house took a long time, but the walls were rising little by little. From a distance it looked like a sort of pink nave, unfinished, anchored on the beach. I soon had to think of the roof, and then the interior installation, the plumbing, a water reservoir under the roof to make use of gravity, the position of the cupboards, the chimneys and sanitary appliances. To this day, I know in English a number of technical terms for stonework, woodwork and carpentry whose French equivalent I do not know. The still gaping windows of the house opened to the north beyond the beach, onto the dramatic horizon of sea and islands, to the south onto the small nearby cliff and the sky, and from my future study to the east, beyond the lake towards the distant silhouette of Croagh Patrick, of Mwelrea and the Twelve Bens. These last stages of the building were made considerably easier by the recruitment to our staff of John O’Neill, who later became our foreman and remained with us long after the house was completed. He came first to work on the interior installation as an assistant to his brother, a carpenter from Ballyconeely, on the other side of Clifden, and soon surpassed him in ability, technique, art and taste. He had a mop of blond slightly reddish hair. His blue laughing eyes reflected intelligence and vivaciousness. He had a deformed spine that did not seem to bother him unduly, even for the toughest work. He excelled in every respect. Later on he easily mastered plumbing and electrics. A true friendship eventually formed between us.

All this however took time, money, work and effort. We were only able to move into our new house just before the summer of 1953, three years after our arrival in the West. The installation of the ground floor was finished, the first floor under the roof still had to be done. In the meantime, after overcoming numerous difficulties, the business had begun to run smoothly. In difficult circumstances, our fourth child Anne-Bénédicte, our second daughter, whom we soon nicknamed Benig was born. She bears the name Bénédicte as a few months after her birth she was baptised in Kylemore with M.Samzun standing in as proxy for her godfather, my old friend William Walsh.

1952 – Babtism of Benig at Kylemore Abbey.From left to right: Madam M.Samzun, Yann Fouéré holding Benig, Marcel Samzun, Madame Y. Fouéré. In the foreground: Jean, Erwan and Rozenn.

1952 – Babtism of Benig at Kylemore Abbey.From left to right: Madam M.Samzun, Yann Fouéré holding Benig, Marcel Samzun, Madame Y. Fouéré. In the foreground: Jean, Erwan and Rozenn.