To

speak about oneself seems indecent to us…As no man is truly capable of judging and appreciating himself, betrayed as we are by the love of what we have…But there are certain occasions when it is permitted to speak of oneself: and amongst these, two in particular – One being the risk of dishonour or danger – The other, when to speak of oneself is useful for the teaching of others…What impels me here is the danger of slanderers and the desire to teach”.

Dante Aligheri “Florentin de naissance non de moeurs”.

Convivio1,2; De vulgari Eloquentia, 1,6.

Epitre X111 à Gangrande della Scala.

FIRST PART

Childhood

1

I arrived in Brittany aged two. I was not born there. I have been reproached for it. “You are not even Breton as you were not born in Brittany”, was thrown at me as an insult by one of these ‘historians’ or chroniclers, from the period between the 2 World Wars, whose main preoccupation is to work on facts and texts in order to demonstrate that Brittany is French twice over. I was obliged to reply to one of them one time – it was to Charles Chassé – that had I been born in Dakar, did not imply I had to be black.

“A person in possession of an American passport is American”. You have the right to be considered one of the elected if you are in possession of this document, issued by an all powerful administration. This is simply a definition of citizenship, but not as understood by the French, who confuse it with nationality. Confusion intentionally maintained by French law in order to avoid the recognition of the existence in France of nationalities that are not French, the Breton nationality for example. Neither the Bretons nor Brittany exist in the eyes of the law. As Morvan Lebesque said, “Brittany does not have a passport”. Charles Chassé certainly did not see the need for it, in spite of his attachment to ‘jus soli’. He was one of those for whom the ‘piece of paper’, birth certificate or passport, was sufficient.

My piece of paper, I have to look for it at the town hall in Aignan, a small town in Gascony, on the road from Riscle to Fezensac. It was there also that, forty years later, my father went back at a time when I was being sought by the French police for “crimes against the security of the state”, which I have expressly put in the plural as I have stopped counting them, to revisit the place where he began his career, found in their Record book, neatly pinned to the page where I featured, a little note eloquent in its conciseness. “The above named Fouéré is actively sought by the police”. In Aignan, where nobody knows me and where I lived only for the first two years of my life, extraordinary naivety of the administrative mechanism! I still have that little note. It features in my archives together with the magisterial white tie worn by the prosecutor to the Court of Justice in Rennes, stolen by an anonymous friend in 1946 during my trial in absentia, when he demanded that I should be charged for “Intelligence with the enemy” but in reality for my Breton activities.

My friends from Occitanie, companions in a similar struggle, Guy Héraud, Robert Lafont, Yves Roquette, Yann Houssin, Gustave Allayrol and others, are unlikely to recognise me as being ‘occitan’, by the mere fact that I was born in Aignan, without having taken the trouble to live there or learn the language. The most I could aspire for is an honorary citizenship of a future Gascony. My father had been promoted to the position of Registrar and sent to Aignan. He had previously held postings with the Administration in various parts of Brittany and it was during one of these that he met my mother in Callac. The tradition in the Administration being to have its agents interchangeable, this Breton of old peasant stock from Dinan country, had to be sent to Gascony. This is why for many years; Brittany had the privilege of being sent Corsican Prefects and Tax-collectors. He discovered later, when he became more familiar with the workings of the Administration, that it was advisable to hide ones preferences for posting in order to stand a better chance of not being appointed to where one had no wish to go.

“You have no idea”, he confirmed to me one day, “how far it goes. Suppose there was a Tax-collector by the name of Basket and a place in Reunion or Martinique named Apple, it would be a godsend! Basket would be appointed to Apple so that “Basket of Apples” would be the Joke of the Ministerial offices for a week”.

So it was that my father hardly exercised any responsible position in Brittany except at the end of his career as Head of Treasury of Finistere for two years when, during the tragic hours of 1940, he ensured under perilous conditions, the evacuation by sea of the Banque de France’s stock of notes and gold. Nonetheless he was hurriedly removed from that position without reason, in 1941, when I founded the daily “La Bretagne” whose articles did not spare the Administration of the time.

It was owing to this first administrative posting of my father’s that I was born in Aignan. I have always been grateful to the patroness of Brittany for permitting my mother to give birth to me on her feast day. The feast day of Saint Anne and that of Saint Yves are celebrated by all Bretons. It was, no doubt, her way of confirming my bretoness in revenge for the whim of Registrar of Births. My mother told me it was also the local feast day and the music from fairground under her window played a popular tune whilst she gave birth. “Love floats in the air all around…love consoles the poor world”. There is a need of much love for a people to become aware of its destiny. Will the mystery of a vocation ever be discovered, why some hear the call and others reject or neglect it? Aignan holds no place in my calling. I learnt to walk there and to talk with the colourful accent which I lost a couple weeks after leaving there. It seems that I already then delighted in tearing up official posters!

Life was calm there for my parents, enjoying their first born and managing on a modest salary. My grandfather was quietly amused when my mother once proudly showed him her accounts book at the time showing a monthly saving varying between 0,10F and 0,50F.

My father was his own boss. He was also the only employee: real estate and other transactions were infrequent in that sun drenched place. French centralisation had already effectively depopulated the country. Aignan and the neighbouring towns were Armagnac country, just as Roscoff and Saint-Pol are artichoke countries, and the main occupation there was grape harvesting, the other robbing State!… Brittany had rebelled when Paris wanted to impose a tax on salt. In Aignan they did not rebel against the tax on wine or alcoholic beverages; they used more subtle methods, whenever my father had business to attend to in the neighbouring town of Riscale or at the sous-prefecture of Mirande, he never lacked means of transport. He would have a free seat on the public transporter’s coupe or horse and trap. Transporting the Registrar was a guarantee of safe passage, as who would have the audacity to search the vehicle, and make this esteemed civil servant stand up, to discover the barrel of Armagnac over which he had been ceremoniously seated?

II

Both Bretons, and separated from their respective families, by a distance which was much greater than it was now, my parents could not help but consider Aignan a necessary exile. So that when my father was successful in the exams for promotion to Inspector of Registrars he was quick to use this promotion to move closer to his country and had the good fortune to be posted to Registration Headquarters of Rennes. He did not remain there long as he was mobilised in 1915. My mother, my sister and I then went to live in Callac with my maternal grandparents.

From that period in Rennes, I have my first childhood memories: the birth of my sister Heliette, family walks in Thabor, the little garden of l’Impasse de la Croix-Carree which had not yet been inhumanly crushed by huge buildings. It still had a country air about it and the fields, whose calm extended to us, began nearby. What else? The large fig tree in the garden whose fruit we would gather, and the distress of my mother, difficult for me to understand, which struck me as a catastrophy , when my father told her of his coming mobilisation. But it was Callac that was truly the setting for my childhood, where I became aware of the world and life. There that I felt the first “physical” feelings of Brittany which, later on, made possible and irresistible the call of my country.

The Callac of today is not what it used to be. The fields began right by the village. The Koz-Stang, the cemetery street and that of la Fontaine opened straight into the countryside. But the heart of the little town, the place du Centre and rue de l’Eglise have not changed that much from when I first knew them. The people and way of life have changed far more than the grey granite facades of their houses. In the autumn, cider was still made in the street where the cider press was set up, a godsend for the local youngsters, who all came with straws to taste the succulent apple juice straight from little channels of it, running from the cider press. I still associate rue de l’Eglise with the smell of green coffee roasting all day in a primitive cylinder over a charcoal fire by our neighbour. In rue de l’Eglise, one would often come across Francine, the beggar who lived somewhere in the suburbs, always wearing the same skirt and short black coat, her “coiffe” slightly askew, doing her tour of the town with her begging bag. She was feebleminded and often the butt of unkind jokes by us youngsters. She was not much taller than one of us, with red rimmed eyes from chronic conjunctivitis. For few centimes, she would never refuse to dance a type of “Pill ar lann” accompanied by an incomprehensible Breton incantation which would escape from her lips.

There was as yet no running water or sewerage in Callac. The numerous domestics at the time would fetch buckets of fresh water from the fountain, two at a time on each end of a light wooden frame that held them out from the body. This was a long process as it was usually the occasion for extensive chats. Bathrooms, of course, were unknown practically everywhere, even in large towns. Once a fortnight my sister and I were bathed in front of the fire or furnace in a large zinc “tub”, filled with hot water, in which one could sit. The foreign term “tub” probably meant that it was a modern utensil and was the first English word I heard until an American unit was billeted to Callac towards the end of the “great war” and the soldiers became regular visitors attracted by my grandmother’s female employees.

Market day on Wednesdays attracted a much bigger crowd than it does today. Everyone from the surroundings would meet up there. The women in black shawls and “coiffes” of the Tregor, worn also in Callac, were seen together with others of Caronet and Locarn of rounded shape lace, and with velvet bodices, already a cornouaille touch. The Cornouallais from the mountains wore a round black hat held on with an elastic, starched white shirt, hair cut short, which set them apart from those of the north country, who were already wearing caps or felt hats. Callac was thus the boundary of two worlds and the fairground where they met. To the north, the moors of Plourac’h and the forest of Beffou opened onto the plain of Tregor, swept by sea breeze; to the south, on leaving the town, rose the foothills and then the mountains of Cornouaille, severe and grey in therain, harsh in their windswept solitude.

At the weekly market in Callac, the Tregor and Kerne Breton noisily mingled. The cafes were packed with people and there was barely room to pass in the streets, transformed into a vast stable: dealers and locals appraised the animals and sized them up. Calves, cows, oxen and pigs shared various sections of the fairground. In place du Centre the stalls were set up, offering the most diverse merchandise. On the footpaths and along rue de l’Eglise, local women offered their butter, eggs and chickens. My grandfather’s pharmacy, which opened onto the square, and my grandmother’s shops, haberdashery, drapery, hardware and household goods, all side by side opening onto rue de l’ Eglise, were all full to capacity. Wonderful day for us; no one had the time to look after us. We were able to mingle freely with the crowds in the street along with other youngsters our age, shoes often covered in mud or dung and aprons stained. The farm, its smells, work, noises, cries of animals and swearing of men, invaded Callac, filling our ears, nostrils and eyes.

Rue de l’Eglise with the pharmacy and other shops on the left.

Rue de l’Eglise with the pharmacy and other shops on the left.

We lived on the first floor over the pharmacy and shops: even the living room was up there. All except for the dining-room, this was through a glazed corridor off the pharmacy on the ground floor. The dining-room, even more than the pharmacy, was my grandfather’s domain where he reigned as master. Further down were the office and kitchens, always very noisy as the employees of the shops and workshop had their meals there. Our only outlet was to the square and street, frequently the theatre of our games after school. But there was the large mysterious attic, full of strange things and inexhaustible discoveries, which we only dared to enter, trembling. I pity children today, inhabitants of our monstrous cities, in the barracks they live in, who don’t have such a refuge. How can one learn to dream and wonder when confined to the few square meters of our modern apartments! How can one even learn to live in these rabbit warrens that are passed on to us as progress! Life is not only what it is commonly believed to be. Dreams, the infinite, space, are as necessary to it as air, bread and water.

On the other side of the church square, opposite the presbytery, were the old stables and poultry yard, with a big garden beyond: later on this country garden was to become my refuge during the holidays, my haven of rest where I could be alone to write, read and dream. When I first knew it the poultry yard and buildings used for the horses and pony and trap were already virtually abandoned. My grandfather, who had been a great fisherman and hunter, hardly ever went out anymore. He had, in his day, been up to date with progress and new ideas; he was first to use a bicycle in Callac, terrorising the local women who would gather their children when they saw him coming. He had replaced neither his bicycle nor his horse and, from his hunting days, had only kept a few Breton spaniels, the breeding of which was and still is very profitable in Callac. But there remained in the poultry yard a few strange birds: guinea-fowl, pheasant, turkey and peacocks, amazing to us children. A great gourmet, my grandfather loved rare species and choice pieces: also suffering from tenacious gout.

At the time when I arrived in Callac, grand-pere Liégard had a fixed daily program. He no longer tended the pharmacy, except on market days, and left it to my grandmother to see to the running of it and his affairs in general. She was a good ten years younger than he was and had a remarkable energy and activity. Rising late, after breakfast in bed brought to him by my grandmother, he would sit at table at 11:30 expecting his lunch to be served punctually. He waited for no one and was extremely exacting as to the choice and preparation of dishes; he was known to give his plate to the dog if he did not find the contents to his liking. Aging epicurean and sceptic, towards the end of his life he only seemed to derive satisfaction from the perfection of meals, the solitary intellectual pleasure from his reading and the few hours he devoted to his grandchildren. He spoilt us outrageously.

Shortly after midday, when the meal was over, the whole family: my grandfather, grandmother and my mother then set off for their daily visit to “grande grand-mère” and to uncle Joson. In each of these houses he had the traditional “petit verre”, frequently from his own brewing. News was exchanged, of the family, of Callac and of the war. Then my grandfather returned, his tribe following, to usually take refuge in his room or the lounge, where he stretched out to read for the rest of the afternoon.

When we were old enough, my sister and I went along. We loved this walk which followed a fixed path, through the echoing alleyway behind the presbytery, to grande grand-mère who lived in a small low house bathed in sunshine at the bottom of a garden full of flowers; then through the fields to my uncle’s garden, with a long extended arbour full of shade and mystery: finally, avoiding rue de la Fontaine, through the boys school’s garden, which brought us back, by the square de L’Eglise, to the street. Life flowed on calm and even, barely shaken by the storms of a distant war, which served as a background, and to which there seemed no end.

But the end came: we learnt of it in the course of one of these walks, which hadn’t changed despite the sudden death of my grandfather in 1915, just as we arrived at uncle Joson’s. Being the mayor, he had just been advised by an official telegram. As a doctor he was one of the few to possess a telephone. My sister and I had gone out to play again in the yard when the “garde – champetre”, hastily sent for by special messenger, came to see the mayor. He didn’t believe us when, as he arrived, we shouted “the war is over”, “the war is over”. A few moments later he came running out of the house, forgetting his clogs on the doorstep in his hurry. Less than ten minutes later the bells started ringing, filling the sky with an ocean of echoes whose wave reverberated from befry to belfry through valley and fields. The church filled up with people, the schools emptied, whilst hymns of thanksgiving rose up to heaven. I had, a few months earlier, celebrated my eight birthday.

III

Grand-mère Quéré, the one we called ‘grande grand-mère’, as she was the mother of my grandmother, was truly the matriarch in a family where the men died young. She was as immutable as the church belfry. Tall and straight, her face framed by the wings of her ‘coiffe’, the black shawl of Trégor around her shoulders and the black embroidered apron around her waist, in the pocket of which she kept her snuff-box. She must have aged suddenly, long before I knew her, as she had ceased to age since. Even my mother could not remember seeing her other than she was. Good and kind, she was authoritarian and valued her independence above all. She would always refuse to ask for anything and never complained. The last years of her life, which she had not anticipated to be as long, were overshadowed by material difficulties: she had survived nearly all her children except for my grandmother, one other daughter and her son, Dr.Quéré, Uncle Joson, my grandmother’s only brother. It is probably from this grande grand-mère that we have a great desire for independence, the will to be self sufficient and to owe as little as possible to others.

She was born in 1838: I was twenty when she died, in her ninety second year, which indicates how well I came to know her and what a mark she left on my childhood. She would willingly speak of the past, of Callac in the old days and of the Brittany she had known in her youth. I would listen to her eagerly: she was my living link with history. It would amaze me that she had spoken to people who had known Brittany before the Revolution in Paris in 1848, and that it was on that day the chapel built on Mont Saint-Michel, along the road to St. Servais, collapsed during the storm.

A native of Loguivy-Plougras, she was brought up by her own grandmother, Ambroisine de Kergariou de Cosquer, of old and unassuming nobility. The latter, under the Revolution, had married a commoner named Bricon, the miller of the area, above suspicion of hostility to the new order. Family tradition holds that he was her gaoler before becoming her husband… As a mark of gratitude, grande grand-mère named her eldest daughter, my grandmother, after her. Under the 2nd Empire, whilst still very young, she married Olivier Quéré, health officer, native of Pommerit le Vicomte. That same day of her wedding she had arrived in Callac on horseback behind her husband. Roads then were scarce and , except for those used by the mail coach from Guingamp to Carhaix, they were mostly tracks or paths linking small villages in the valleys or in the foothills. The young Dr. Olivier Quéré did all his calls on horseback and died prematurely from a fall which fractured some ribs and led to a tuberculosis he refused to look after, as he considered his patients could not be deprived of his care. He monitored the progress of his illness and died leaving his wife a widow at not yet 45 years of age. His children at least were practically all grown up and married and his son, Dr.Joson Quéré, took over from him. Grande grand-mère, from then on, settled into an austere widowhood which lasted longer than her life previously. I do not remember ever seeing her in anything other black, apart from her white ‘coiffe’. For mass on Sundays she would often wear her large mourning cloak, whose hood was adorned with black velvet.

The reputation and memory of her husband, Doctor of the poor, were still very much alive in Callac when I arrived there over thirty years after his death. I have kept very carefully, in my archives, his Health Officer’s diploma, awarded by the Imperial University. He had courageously conquered it, as he came from a large family, of modest means, who could not entirely provide for his studies. He had to work to earn the balance of money required. Pommerit was close to the sea, and Paimpol was then a relatively prosperous fishing port from where cod fishing boats went as far as the coast of Iceland and Newfoudland. Olivier Quéré did several trips with them, as both ship’s boy and nurse, and earned the money he needed to complete his medical studies. There was no question of carrying on to obtain a doctorate.

The only portrait we have of him, done by the artist Th.Salaun, from Guingamp, portrays a bearded man radiating extreme kindness, with a high forehead and extraordinarily bright blue eyes lighting up his face. The face of an apostle and Celt, which his only son Joson inherited, with a gaze, colour of the sea and sky, fulfilled on the shoals off Iceland and the moors of Callac where his vocation lay. In that poor and isolated place, medecine was to him more of an apostolate than a profession, and he practiced it as such. He never charged poor families for his services and would even bring them medecines and the simple remedies he made up himself, accepting nothing in exchange. He was the Social Security at a time when there was none. He saved lives and brought into the world a new generation of Bretons. Amongst them Anatole Le Braz, that ‘son of the hills adopted by the sea’, son of a school-teacher in Saint Servais. This was the task he had assigned himself and the fulfilment of it was enough for him, as it pervaded his life completely.

His kindness and concern extended not only to the sick but also to the unemployed of the town, where work was scarce. One can still see in Callac, in rue de l’Allée, a row of little terraced houses which he had built, one at a time, to provide work. He would sell them immediately in order to pay those who had built them, with no thought of speculation. The age of promoters and speculators had not come yet. For him it was just a means of providing his most needy fellow-citizens with a livelihood. He was often out of pocket, and his wife reproached him bitterly, taken up as she was with the worries of the household and the education of the children.

– “Quéré, you are being robbed by these people”, she told him..

But he took no notice and continued to treat his patients free of charge and build a whole neighbourhood of Callac at his expense. In despair, grande grand-mère had to resort to opening a small drapery shop, rue de l’Église, to supplement the household income. This same business, which was to be passed on later to my grandmother, is still being run by one of my cousins, Yvonne Leroux-Le Roc’h, a descendant of the only branch of the family still living in Callac.

It is doubtless from grand grand-père Quéré that I have inherited the missionary side of my character, which seems to have survived in my sons, an attachment to unselfish causes, some could say visionary, in the service of which the costs are always far higher than the returns. Among his direct descendants, none made a fortune or excelled in any ‘profitable’ profession. They nearly all chose service professions and, though only one priest, there have been doctors, navy-officers, social workers, civil servants and employees directing a service. There have, in fact, been few men, so it has been mostly women, who have also been head of the household and provider, in often difficult circumstances and long widowhoods. Thrifty, sometimes avaricious, they inherited the example, practical spirit and longevity of grande grand-mère. My own grandmother lived to 93 years old, after a widowhood that was nearly as long as her mother’s. There was just half a century between her and I.

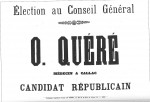

She married very young, at 16, looking smart under her Trégor ‘coiffe’ with the big lace wings, which accentuated her small stature. She married Adolphe Liégard, whose family was from Guingamp and who established the 1st pharmacy in Callac. Imbued with new ideas and favourable to the infant Republic, it was he who encouraged his father-in-law to present himself for election to the ‘Conseil générale’. He had witnessed his great popularity in the district. Grand grand-père Quéré allowed himself to be persuaded, presented his candidacy but refused to campaign. The story goes that the ‘Conseiller générale’ at the time, Générale de la Jaille, holder of his seat since 1864, during his election campaign, which was to be his last, had lost his way around Carnoët. He decided to ask for directions from a ‘casseur de pierrre’, type of district worker the, who was breaking up stones to fill holes in the road. Ordering the ‘coupé’ to stop, he made his inquiry and, thanking him for his directions, handed him a golden louis. Hardly believing his eyes, the fellow called him back;

-“You must have made a mistake, Sir”.

-“No, no, I have not made a mistake,” replied the Conseiller générale’, “but maybe you will vote for me next Sunday”.

Taken aback, the fellow thought about it briefly before replying;

-“Then I’d rather give you back your louis, Sir. Dr.Quéré has brought all my family into the world and always looked after us; he has always refused to take any money…”

-“I understand,” replied the other, “you are quite right, keep the louis and here is another to reward you for your sentiments.”

Certainly the least one can say is that morals and times have changed!

The prefecture could not believe the success of this first republican candidate in a traditionally monarchist district. He was elected at the first round. The Préfet of Côtes-du-nord came to visit the remote town to celebrate this unexpected victory for the Republic. He made a long speech, paraded around the square with the newly elected candidate, and threw money and sweets to the children who fought over them. He conscientiously accomplished his task as governor of this barely subdued colony – less than a century still separated it from the loss of its autonomy – who still spoke an incomprehensible and barbaric language. But thanks to the compulsory introduction of a primary school, this would be no less conscientiously eradicated.

Grand grand-père Quéré died shortly after, in 1886. My mother was then 4 years old. His son Joson succeeded him. Joson had completed his medical studies and spent a few years in Indochina, when it was being conquered by France. On his return to Brittany, he had taken over his father’s practice and was subsequently to become Mayor of Callac. Like my grandfather, who had the first bicycle, Uncle Joson, equally as progressive, had, at the beginning of the century, the first car. A tall noisy contraption, which replaced the horse and trap he had been using until then. His wife, Aunt Caroline, complained she could not ride in it without catching numerous fleas lodging in the cushions.

She only found out later that Tydou, the local poacher, attracted by the comfort of the seats, surreptitiously spent part of his nights there, after the practice of his art. Having also inherited the kindness of his father, Uncle Joson knew about it but turned a blind eye, without telling his wife. The noise he made, if he had to go out on urgent calls at night, was always picked up by Tydou’s practiced ear and allowed him time to vanish into the night with dignity… The rue de la Fontaine that Uncle Joson lived in has been renamed after him…but for me the rue du Docteur Quéré remains as a combined tribute to both father and son. In Callac today, they are still both remembered for their unselfish devotion, often confusing one for the other.

IV

Grand-père and grand-mère Quéré usually spoke French to their children, as did most bourgeois families of Callac: but they could all speak Breton without having strictly learned it. One could not ignore the language of the country. At the turn of the century, Callac was 90% Breton speaking and, as in the countryside, French was practically unknown. Whilst doing their rounds, both doctors Quéré used only Breton. My grandmother spoke it fluently, as of necessity for the needs of her business, but my grandfather Liégard, who came from Guingamp, did not. She would serve as his interpreter, though in the end he understood it, but made no effort to go further than that.

Adolph Liégard was from a family of building contractors in Guingamp, and it is through these Liégard, related to the Le Goffic, that my wife and I are distantly related. He was orphaned at a young age, and the task of bringing him up, together with his brother Auguste who became a navy doctor, was left to his mother and in particular to his eldest sister, Marie. This holy woman sacrificed herself, her future and her life, refusing marriage to fulfill what she considered her duty. As money was scarce Tante Marie, as my mother who was her godchild called her, opened a small business in the family home, selling ‘coiffes’ and lace. The house still stands, forbidding in its facade of grey granite, situated practically on the bridge over le Trieux, in rue des Ponts Saint-Michel. The old Marquise de Kerouartz, living in the château des Salles nearby, who knew the family’s pride and circumstances, was one of my great aunt’s most assiduous clients.

It is probably because he was brought up by women that my grandfather took it for granted that, now married, he could increasingly leave the running of the house and responsibilities of the business to my grandmother. He later confided to his friends that the reason he had married such a young woman was so that he could mould her to his liking and , in fact, she constantly surrounded him with assiduous care as long as he lived and never let him down. Long before the end of his life, she took to shaving him every morning: when gout overtook him, every night she would remove his shoes and put on his slippers. When she was not seeing to the pharmacy, the workshop or the business, she was seeing to the stocking of the kitchen and preparation of meals, whose quality above all had to satisfy the gourmet palate of her husband. He, in fact, took after his grandfather Neumager, who would happily consume his hundred oysters every Friday: but they had to be from the Tréguier river: no other would do. He would eat a whole chicken every Sunday, when chicken was then still a luxury, except for the thighs which he did not like and would leave for his wife. Some of his other descendants had inherited his tastes! Amongst the childhood memories I have of our visits to Guingamp, were the extraordinary quality and quantity of the meals served by the uncle and aunt Charles Neumager. Their vast bourgeois house can still be seen, back a little from rue Saint-Nicolas, by the corner of the small square where the post office is situated today.

Once the little narrow tracked train was inaugurated between Callac and Guingamp, my grandmother often took the first Friday morning train to buy fresh fish there for the day-s meal.

My grandfather thus lived the life of a Sybarite, where good fare, good drinking, good eating and good living was of considerable importance. This type of life must have been to his satisfaction, as he rarely felt the need to go out of Callac, whose surroundings remained his universe. As a young man he enlisted in the Breton army, when the Prussians took possession of Paris in 1870. He had thus participated in the Camp de Conlie adventure when the government of the infant Republic, distrusting this Breton army, had deliberately allowed it to be massacred on the Mans plateau, just as the Russians in the last war also deliberately left the Polish resistance in Warsaw to be massacred by the Germans.

My grandfather had always enjoyed the open air. Having settled in Callac, relying increasingly on his wife to run the home and business, and as long as his health permitted it, he would spend most of his time chasing around the countryside with friends who shared his tastes: the notary Le Goaziou, the hotelier Bourhis and Prigent the wine merchant. Keen hunter and fisherman, he knew every wood and stream within a 15km radius of Callac. It is said that simply from the taste of the wild trout he could distinguish from which river it had been caught. He would certainly never have considered eating the factory bred chicken and trout of today, the inevitable evolution of an industrial world seeking to ‘generalise’ the consumption of all products, of which there was no danger in Callac at the turn of the century. As there were few fishermen and hunters, there was an abundance of fish and game, and it was not as yet necessary to artificially re-stock the rivers, woods and warrens to provide the multitude with a pleasure or sport, which has become as artificial, aside from the open air, as slot machines or big show matches. Amongst my childhood memories of the early twenties, are the summer fishing trips with my uncle, Dr. Liégard, who had inherited his father’s passion for hunting and fishing. It was not unusual for us to come back at the end of an afternoon with two or three dozen trout.

It is no doubt, both from grand-père Quéré, whose ministry took him riding the moors and pathways, and grand-père Liégard, whose passion for life in the great outdoors influenced him to do likewise, that we take after, in that all of us in the family have a horror of big cities and a deep feeling for the sea, fields and the open air. But the sybaritism of the latter would seem to be an accident. The love of good fare and good living, which became generalised and excessive in France was, at the time, only enjoyed by a priviledged few who had the leisure and the means. My grandfather’s table and wines appeared exceptional to his contemporaries.

– “The Liégard’s”, the locals readily agreed, “people who earn well, but who consume all their earnings”.

Many neighbours and friends were in the habit of visiting my grandfather on the stroke of eleven, in the hope of being invited to share his meal. One of them, a dog trader, was accustomed to this and was one of his most assiduous visitors.

Voltairian, caustic, sceptic and open to every new idea, my grandfather was only remotely interested in politics. He valued his peaceful lifestyle and freedom of spirit, sharpened by his readings, too much to become involved. He probably thought it was useless. Brittany and the problems it was beginning to have at the end of the century, with the ruin of its traditional industries, hardly seemed to worry him. Like his father-in-law, Dr.Quere, he physically ‘lived’ Brittany. It permeated his very being and he never left it long enough to think of it in separate terms. But his brother Auguste, the navy doctor, whose career, followed by a long illness, caused him to interest himself in his country of origin and realise its singularity, had felt the call of Brittany. To him we owe a well documented, precise and learned book, ‘Flor de Bretagne’, with not only the scholarly name and French name of each plant but also the Breton name, which still remains the most complete work published on this subject. He died young, in 1892, thus I never met him, but I owe to him partly my feeling for Brittany. For me it was the opening of a whole new world. I had by then left Brittany and could only return there on holidays. From then on I began to read everything I could lay my hands on concerning this country which, having been separated from it, I deeply felt was mine. I began to notice that a good deal of what I had been taught, at school or at the Lycee, was false, and that I had to considerably modify the teachings of my teachers.

In the midst of the war, when I started at the lay primary school and my sister at the nun’s school, the main preoccupation of our teachers was to turn out good French citizens. This they did in all good faith, as per the guidance and instruction they had received during their lay or religious practical training. Their duty was to assimilate and integrate a population still foreign enough to speak a distinctive language and who, from their ancestors, might be harbouring sentiments of their singularity. Speaking to us of Breton history was out of the question. French history was the same everywhere: the Senegalese and the Algerians were not treated any better than we were. We were often told of the war and of provinces lost, and we could not draw a map of Alsace Loraine without the tricolour framing it.

I only realised this much later, when I was able to question and judge for myself. At the time it all seemed quite normal. I was as intolerable at school, as I was well behaved at home : a reflection already of my life in the future! Though my private and family life has, on the whole, remained free of storms, other than deeply intimate and private, my public and political life was to be filled with changes, storms and adventures – to the despair of some of my best friends who, non Bretons, could not of course share all my ideas or understand what inspired my actions.

Nevertheless, the only thing that did surprise me already at school in Callac, and which I found very strange, was to see the school principal, Alexis Le Moal, a decent man, yet who freely distributed clouts and punishments to my mates from the town and countryside, if he heard them speaking Breton while they were playing in the recreation yard. So that the only words they could use without fear, were the swear words with which we dotted our vocabulary. Although I was always spoken to in French at home, it surprised me that the language spoken by 80% of my mates in the street, was not allowed to be spoken in the school-yard. I had not as yet reached the stage of rebelling against this anomaly, and was unaware of course at the time that this was a matter of a definite policy and precise instructions to bastardise, extirpate and cause the death of the thousand year old language of this country. For the linguistic unity of France, according to the minister of education, A. De Monzie, it was imperative that the Breton language disappear: conscientiously, patiently, generation by generation, our teachers worked at it .

V

The death of my grandfather during the war, and later the end of the war and demobilisation of my father, were to bring new changes into our lives. Throughout the war my grandmother continued, as before, to look after the pharmacy and business, and to help her out, my mother became increasingly involved. My grandmother had an enterprising spirit but did not have an administrative frame of mind: while on the other hand, my mother was most concerned with thrift and good management. As a result, in spite of the uncertainties of the time, we began to no longer “eat” everything we earned and to reduce our lifestyle.

During this period my father remained a distant figure that we saw very little of and for whom we prayed every night. My uncle, Dr.Liegard, on the other hand made more frequent appearances in Callac. He spent all his leave there and, after the war, all the holidays he could. Though a staunch Breton, he had married a Parisian, and it was owing to her influence that , after a brief spell practising general medicine in Binic, he decided to settle in Paris, where he was to become one of the most eminent ophthalmologists and head of surgery at “Quinze-Vingt” Hospital. My aunt Suzanne fully belonged to that peculiar Parisian fauna with gregarious instincts, at ease in crowds, who can not live anywhere else but Paris, yet whose main preoccupation on the other hand is to escape from there at every possible opportunity to various fashionable resorts or beaches to meet up with most of the people they frequent every day in the “salons” of the French capital. Brittany, its filtered sunshine, and the peace and quiet of Callac, which she regarded as the back of beyond, never attracted her. Thus my uncle mostly came alone to enjoy in peace and quiet his fishing in the rivers.

He knew Callac and its countryside well, also the Cornouaille hills he had explored alone or with his father, cycling, walking or in a pony and trap. His thorough knowledge of the country, its language and its traditions had enabled him to write an unusual medical thesis, which remains an authority on the subject, on “Saints guerisseurs de la Basse Bretagne”. He had no children at the time, as their only child, a daughter, was only born after eighteen years of marriage. I was thus more like a son and companion, following him in his fishing trips, cycling or on foot. Come autumn, we scoured the woods for mushrooms of all varieties, about which, as befits the son of a pharmacist, he had an extraordinary knowledge. He was an excellent mycologist like his father, and I was a patient and interested student of that science. His daughter, my cousin Janine Huas, inherited this, and devoted a learned work to hallucinogenic mushrooms, at a time when drugs were beginning to wreak their havoc. This was in fact only her first work. It was mainly thanks to Uncle Henri that I discovered this harmonious countryside, at once gentle and wild, which later I often explored alone during the holidays>irresistibly drawn back, like Uncle Henri. The valley de l’Hyeres, whose murmuring waters snake through the hills with their crown of woods and rocks, the russet moors of Plourac’h, Burtulet or Douault, the rocks of Corong, the summit of the wooded hills of Saint-Servais, Mont-Saint-Michele, Beffou and Keranlouan from where one could detect the spire of Bulat church, hope for the pilgrims to its fountains, all soon held no secrets from me – Brittany penetrated through my every pore – Rennes already seemed an exile, not to mention Paris, where I would soon find myself!!!

My father returned from his service in the infantry with a bronchial illness, which he never quite recovered from, and a superficial head wound from a German bullet which pierced his helmet through and through – the helmet remains a family relic. My father had thereafter completed his war service in the army’s financial administration. Demobilised, he resumed his post with Registration headquarters in Rennes. He had not been there long, when the Guingamp deputy, Yves Le Trocquer, a political friend of my Uncle Quéré, was appointed Minister of Public Works, and summoned him to his Cabinet Office in Paris, to take charge of his personal secretariat.

1922 – From left: the Minister of Public Works Yves le Troquer, Jean Fouéré his Chef de Cabinet, greeting crowds on the occasion of a Ministerial visit to Dinan.

1922 – From left: the Minister of Public Works Yves le Troquer, Jean Fouéré his Chef de Cabinet, greeting crowds on the occasion of a Ministerial visit to Dinan.

At that time also my grandmother had decided to retire. After selling her pharmacy and business, she settled in Saint Brieuc, in an apartment she had rented over the Danet pharmacy, rue St.Guillaume. I had been entrusted to her care there, in order to begin my secondary schooling at St.Charles, where I also made my First Communion. I disliked the town, and the horizons of Saint Brieuc soon appeared very limited, even though my grandmother rented a cabin on the St.Laurent beach. I went then, for the first time, to spend long holidays with my paternal grandmother in Evran. It was to be a new revelation to me. In Callac, the countryside was certainly not far, but at the Bas Breil – name of the old family tenant-farm – you were right in the fields. Falling asleep in the deep silence of the countryside broken only by the sound of crickets, the starlit sky filling the horizon, and the good smell of grass and leaves rising from the earth, then waking up amidst fields covered in dew, to the familiar sounds of the farmyard, the cowshed or the stables. The air there was fresh, light, virginal. All day we roamed through the thickets and pathways, and late afternoon accompanied the cows to pasture. We lit large fires on the moors at nightfall, and cooked potatoes and apples in the ashes. I was truly discovering life in the fields, the work and the joys, the direct, total and deep contact with nature.

1922 – 1st Communion of Yann Fouéré at St. Charles in St. Brieuc.

1922 – 1st Communion of Yann Fouéré at St. Charles in St. Brieuc.

The Bas-Breil’s relatively imposing farm buildings are not noticeably different from what they were sixty years ago, arranged on both sides of a spacious yard, with its granite well and pool of stagnant water, where the cattle drank. The main building, adorned with a sculptured granite ogive framing the door, erected at the end of the seventeenth century, still exists. More recent additions were made on each side. The cowsheds, stables, barns and piggery occupied one side of the yard. On the other side was the oven.

Bas Breil, Evran, cradle of the Fouéré family.

Bas Breil, Evran, cradle of the Fouéré family.

On arrival, either at the station in Dinan or that of St.Domineuc where the little local train, long since gone, used to link Rennes with Dinan, we were usually collected by the pony and trap. The horse was accustomed to the journey, especially from Dinan where my grandmother Fouéré and Uncle Constant, my father’s brother, usually went to market day on Thursdays.

He could have made the journey with his eyes closed, and stopped of his own accord at customary stages of the journey, usually cafes alongside the road, between Lanvallay and Evran. It took a long time, as there was no hurry, and it was proper to stop and have a glass of cider with the neighbours.

We usually stayed in a large panelled room, which had been built on to the back of the main part of farmhouse at the time of my father’s marriage, to welcome the “young lady from town” that he had married. It opened directly onto the garden and fields.

They still made bread at Bas Breil, usually every three weeks. For us it was a holiday. After the enormous golden loaves of bread for the household had been removed from the oven, grand-mere d’Evran, as we called her, invariably baked some “tourteaux” specially for us – long baguettes of wheat bread – all crusty, which we split in half while still hot and filled with succulent butter, freshly churned every week and shaped into enormous mounds decorated with various patterns and motifs.

I never knew my grandfather Fouéré, who died at the very beginning of the century. Grand-mere d’Evran, on the other hand, has remained very much alive in my memory, though she died before my great grandmother of Callac. She wore the “catiole”, small minuscule “coiffe” of the Dinan district, perched on grey hair smoothly drawn back, held by a “résille”, type of hair-net, and framed with a band of black velvet. On Sundays she also wore the big black shawl with fringe, similar to the Trégor one, and the “devantier”, decorated with black lace, and an embroidered handkerchief just visible from the pocket. After the death of her husband, she had continued to run the farm with the help of her eldest son, Constant, and of the youngest, Jules, who was later killed in the war.

My father, who was the second born, had been urged towards a secondary education as was the custom. He completed it at the Cordeliers in Dinan and subsequently prepared for the Registry exams. The Fouéré family had been rooted in this corner of land for several centuries, and the farm had been passed on from father to son, from generation to generation, as far as one could go back, to around the 17th century. It was probably the cradle of the Fouérés, not a very widespread name except in the district of Saint Malo, Dinan and Rennes, and which had its origins between Rance and Vilaine. An Adolphe Fouéré from Chateauneuf and St. Thual was shot on the Garenne in Vannes in 1795 by republican French troops, alongside his master, Monseigneur de Hergé, Bishop of Dol, whom he followed into exile to Jersey. There are numerous Fouérés to be found in old deeds and parish registers of Basse Riviére and Evran – some Eustache, Jean, Jacques and Francois, persons of standing in their village, Bailiffs, Syndics or Public Officials, since the reign of Louis 14th. My roots go back a long way in this Breton soil of Evran on the northern boundary of the Rennes basin. I owe a lot to this old peasant stock of our Gallo country, with its slow reflexes but sure conscience and true judgement.

My grandfather Fouéré, as the Fouérés who preceded him, was not the proprietor of Bas Breil. It belonged at the time to one of the de La Villemarqué, relatives of the author of the Barzaz Breiz. On the death of my grandfather, grandmère d’Evran and her three sons decided to buy it, and the lands have since remained in the family. The Bas-Breil itself is still occupied and used by the children of one of my first cousins, daughter of my uncle Constant. Throughout the war, my grandmother Fouéré, alone and deprived of her sons, had been obliged to work very hard to run the house and farm. She succeeded thanks to her great strength of character, imperturbable calmness, even temper and deep sense of duty. A woman of few words, she had all the qualities of her kind. At once humble and proud, and did not expect more from others than she did of herself. But she did not spare herself. She would hasten slowly. It is probably from the Fouérés that I come by this apparent coldness, which is often but a reflex of shyness, a retiring within oneself and modesty of character which prevents surrendering or letting oneself go completely. But calmness often conceals inner storms and passions to which one does not want to release the floodgates. Even my father was more sociable than I. He was also more popular than I ever was.

My uncle Constant waited until after the war, throughout which he was in the infantry, before taking a wife and enabling him thus to relieve my grandmother at the head of the family holding. I still remember very clearly his wedding to my future aunt Eugénie, who was from the Frin family in Saint Juvat. The huge table, decorated with sweet smelling bouquets, had been set up in the barn. Its walls had been covered with white linen sheets, smelling good of wind and moors, which filled my grandmother’s cupboards. Flowers had been pinned on them, as was done in Callac for Corpus Christi on the facade of the houses along the streets strewn with wild flower petals for the procession. What I mostly remember of the pantagruelic repast, enhanced by various songs from the participants, was that it was far too long for me and took up the whole afternoon. It was not long before the bunch of children that we were, slipped off to play in the yard, coming back from time to time to get hold of a piece of cake or a gulp of sweet white wine.

The countryside of Evran and its landscape of groves, with only rolling countryside and not much relief, which characterises the foothills of the Rennes basin, has neither the charm, variety nor beauty of that around Callac. Their inhabitants differ as does their countryside. The Bas-Bretons are much more hot tempered than the Gallos. The latter are calmer, less prone to feverish activity and surges of rebellion than the former. The patois still spoken in the countryside around Evran is more closely linked to French than to Breton, though it is dotted with numerous terms of Breton origin. The inhabitants and their districts are no less Breton for that. They know they are distinct – Already one senses the dawning of the boundary sentiment, which becomes more pronounced the closer one draws to the districts of Saint Malo, Fougéres, Chateaubriand or Vitré.

This soil between Rance and Vilaine is full of reminders of our history. It was in Evran that Beaumanoir, the hero of the ‘Combat des Trente’, had his castle, today converted to a departmental establishment. It was on the ‘Butte de la Justice’ in a field overlooking those of Bas-Breil, which were moors at the time, that the Evran Treaty between Blois and Montfort was signed during the war of succession in Brittany. It is in Bécherel, a little more than a league away, where the Chateau of Caradeuc stands, elegant abode of the Procureur La Chatolais, one of the great opposition figures of our Breton 18th century, who came to grips with the arbitrariness of the French monarchy. It is in the triangle of Saint Malo, Dinan, Plancoet that was born the ‘Conjuration Bretonne’ of our Armand de la Rouerie, who aimed to re-establish a Brittany with its autonomy and its national rights, which has been wrongly presented, solely for the purpose of discrediting it, as a purely royalist rebellion, whilst it was above all national and Breton in its origins and objectives, even if later on some tried to divert it. Even today I still can not wander about the countryside of Dinan, Evran and Bécherel without recalling these great ghosts of our history – but they were not yet in my thoughts when as a youngster free from school I roamed the fields and hedges of Bas-Breil, drunk with freedom, countryside and pure air.

VI

Having completed my first year, my parents decided I should continue my secondary schooling in Paris. So it was that I did my 2nd year at the Lycée Montaigne, and thereafter from 3rd year onwards at Louis Le Grand.

After a short stay at Villemomble, my parents had settled in a small apartment in avenue du Parc de Montsouris. One only had to go down the full length of boulevard Raspail to reach the Ministry of Public Works, boulevard Saint Germain, where my father had his offices. During the four years he held office with Yves Le Troquer he became attached to him and seconded him faithfully, attending to relations with his voters of Côtes du Nord in particular, attentive to their various needs, and activating the election campaigns. Numerous actions that benefitted the department, during this period, can be accredited to the active polytechnician, Yves Le Troquer, and indirectly to my father. The latter made frequent trips to Brittany: it was in the days of inaugurations of memorial monuments to those killed in the Great War, to which the Minister, from the department where he was the elected member, was invited to attend. He had to be deputized and represented, often at the cost of two consecutive night’s journey by train, and the customary speech delivered. On his return, my father enjoyed repeating to me snippets of eloquence from local personalities, often in remote Breton districts, still relatively unfamiliar with the French language, such as: bowing, ‘before this stone which spilt its blood for our country…’. The euphoria of a victory acquired at a cost was still there; but the price had been too high and was to weigh heavily on the future of Brittany and France, during the two decades separating us from another World War. Life was decidedly not as before. I was not yet of an age to worry about it during those early years of the twenties, or be aware of the problems it posed. For me, Brittany remained that of my childhood. I dreamt only of going back there, which we did for all our holidays, short and long, thanks to the travel facilities we were entitled to because of my father’s position with Public Transport. Paris was but an exile for me, and has always remained as such. Nonetheless, I learnt a great deal there: having frequented the ‘patronage’ of rue de la Tombe Issoire, where our parish church was, I was no longer surprised that many inhabitants of Callac had never seen the sea, although it was only thirty kilometres away. Many children from this neighbourhood had never been closer to the centre of Paris than the Magasins de Bon Marche, and on the other side, no further than Parc Montsouris and Porte d’Orleans! Most had never seen a field, a flower one could pick, a green space on which one could walk, nor a free flowing stream: the streets, buildings, yards and squares of the neighbourhood were the only horizons they knew. Although I never told them so, I felt very sorry for them, and as my studies progressed I was surprised that Paris could be considered the ‘City of Light’, centre of culture, civilisation and progress. In view of these simple truths, I could never believe it, in spite of what I was taught by my teachers, although I was appreciative of French ‘greatness’ then. Yet life in Paris at the time was much more bearable than it has become, with its boulevards and streets transformed into a vast garage. There was far less motor vehicle traffic. A great many deliveries were still done with horse-drawn vehicles. It was forbidden to park cars for the night in public thoroughfares: their owners had to place them in a garage. After eight o clock in the evening, therefore, the avenue belonged almost solely to pedestrians and children playing there in the summer.

I was especially interested in history and literature and otherwise was a rather indifferent student. At times, in the same term, I came last in mathematics but first in history or French composition. I was not learning from books alone, however, and here again the facilities afforded to members of the Republic’s ministerial cabinets were useful to me. I was frequently able to attend performances, free of charge, from the official box at the Odeon, Theatre Francais and the Opera Comique. My studies were thus extended most vividly. I also began to read numerous historical novels. Alexandre Dumas, Jules Verne, Andre Lauries and Fenimore Cooper soon held no more secrets from me. I extended my studies of Malet and Isaac, for my history course, with other more thorough reading. My French compositions, exercise books, and pages of a diary many times forsaken and many times resumed, were full of poetic descriptions of the Breton countryside, its gorse in bloom, its moors and shores. I was thirteen, when with the help of my ten year old sister, whose collaboration I had called upon, I launched my first monthly journal entitled ‘Un Joli Roman’, a historical novel that I had undertaken to write, but never finished. We copied the entire journal by hand making about ten copies, and putting it to good use, then sold it to my parents and other members of the family. I should add, however, that only half a dozen or so numbers were actually produced!

The elections of 1924 had brought a change in the distribution of political groups in the Chamber of Deputies, and it was then that Yves Le Troquer had to leave the Ministry of Public Works. Afterwards, much to his disappointment, he was not appointed to any other Ministerial post before his death, which occurred when he was sitting in the Senate. He and his colleague, Rio, deputy for Morbihan, had been the Breton Ministers of that ‘Chambre bleu horizon’ elected in 1919, name given to that assembly for the blue of the soldier’s uniforms, immediately after the First World War. They had both the unpleasantness and the honour of being submitted to reproaches from Poincare, their President du Conseil, for using Breton in their official speeches in Brittany. My father once told me that Yves Le Troquer, irritated by these reproaches, had replied that he had not found any other way of having his name, and government, applauded in Brittany! Poincare said nothing, but omitted to call on this Breton, after the 1924 elections and the defeat of the left, when he formed his next ministries, during which he actually engaged in an action against the Alsatian autonomists, reviling their Breton allies at the same time.

These political changes invariably brought about another change in our family life. On leaving the Ministry of Public Works, my father had been appointed Receiver of Revenues to Clermont dans l’Oise, some seventy five kilometres north of Paris. To my great despair, my parents decided to leave me at Louis Le Grand, as a boarder, in order to avoid another change of Lycée. I had just completed my fourth year, so proceeded to do my fifth year. That year as a boarder, however, was a very painful one for me. I was definitely not cut out for community living, and the constant proximity of my fellow students weighed on me. My natural tendency for solitude, dreaming and solitary meditation, my love of space and freedom was constantly repressed. In spite of being forbidden to do so, I took refuge as often as possible in empty classrooms or in the garden of the central courtyard of the Lycee. I accumulated punishments, restrictions, detentions and gatings. I clashed with some of my professors. I finally had to appear before the disciplinary committee and barely escaped being expelled. The constant disrespect for rules, laws and restraints of all sorts, which was to inspire my whole life ahead, and be ever sharpened by my fight for the freedom of Brittany, no doubt dates back to this period of my existence.

In reality the Lycée was the very image of a Napoleonic barracks, within which the French still all lived. Reveille was sounded by a drum, and the same sound indicated the time for classes and recreation. The list of restrictions was infinite, as were the yards, classrooms and corridors that were forbidden. Outings were strictly limited to Thursday afternoons and Sundays. Whenever my punishments did not prevent me from benefitting from these, I sometimes found them long, but there was no fear that I would shorten them. I was like the young soldier waiting patiently in the cold, on the street, until the last possible moment, before returning to the barracks. I usually had a meal either at my Uncle Liegard’s, or at my Aunt Suzanne’s parent’s place. His surgery was in avenue Ledru Rollin. After the meal, I usually visited museums, in detail, thus complimenting my history classes. Carnavalet, Cluny, Le Temple, La Chapelle des Carmes and the Louvre soon held no more secrets from me. Rather than returning directly to the Lycée, I wandered about the streets or along the quays, sometimes buying a croissant or a ‘pain au chocolat’ from a bakery, in order to kill time. I refused to return before the last minute of my freedom was used up. The only friendly relationship I maintained from Louis le Grand was with fellow-student, Pierre Pouillot, who subsequently started at the Ministry of the Interior at the same time as I did, before branching off towards Finances. Also at Louis le Grand whilst I was there, though in different classes, were Phillippe Daudet and Michel Debré.

Finally my parents agreed to have me finish my last few years of secondary schooling in Clermont. I thus completed my sixth year and the philosophy year at the college there. The house was large, the town small. For the first time, I had my table, my books, and my own room at the top of the house. My window opened on a vast horizon of gardens and woods. There were only eight of us in the class for sixth year, and four for the philosophy year. My work became more intensive, and apart from bad marks in mathematics, I had no difficulty passing both baccalaureates. I had just turned seventeen.

VII

Throughout all those years, however, Parisian or Clermontoise, Brittany never left me. Exasperated by the exile, my Breton consciousness had become ever keener. The departure of my father from Public Works had not really changed our customary holidays to Brittany, only slowed down the frequency of our visits. We spent a month by the sea, usually Trestraou or Ploumanac’h, in rented houses, where my father joined us. The rest of the time we spent at my grandmother Liégard’s place. She had not remained for long in St.Brieuc, too far from her familiar horizon no doubt. She then went on to occupy one of the houses she owned, rue de La Madeleine, in Guingamp for a couple of years, but soon returned to Callac, at about the same time as I was passing my Baccalaureate. Also from time to time, mostly alone, I stayed at Bas Breil with my grandmother Fouéré. I had been given a present of a bicycle, which allowed me to go further afield, greatly extending the limits of my solitary wanderings.

1925 Callac – Yann Fouéré on the right, in front of his grande grand-mère’s house . From left: His great-aunt Caroline(wife of Dr. Joson Quéré), his sister Héliette Fouéré, his grand mère Ambroisine Quéré/Liégard holding her youngest grandchild Jeanine Liégard his cousin, grande-grand mère Fransoise Barbier/Quéré (the widow of Dr. Olivier Quéré) with ‘coiffe’.

1925 Callac – Yann Fouéré on the right, in front of his grande grand-mère’s house . From left: His great-aunt Caroline(wife of Dr. Joson Quéré), his sister Héliette Fouéré, his grand mère Ambroisine Quéré/Liégard holding her youngest grandchild Jeanine Liégard his cousin, grande-grand mère Fransoise Barbier/Quéré (the widow of Dr. Olivier Quéré) with ‘coiffe’.

Once I had become a more seasoned rider, I often cycled from Guingamp to Callac, and spent a few days with ‘grand grand-mére’, whose conversations on the old Callac, its inhabitants, traditions and customs fascinated me. She was so old and had known so many people and things! Her daughter, my grandmother, was not talkative, but was extremely kind and even tempered. Perhaps more reserved, she seemed to be permanently pursuing an inner dream, emerging from it at times to sing some song from her childhood. I ‘lived’ deeply my country – I breathed its scent with delight, and felt I had found my freedom again – the Brittany I was deprived of for nine months of the year penetrated my very being, through every fibre of my body, and filled my soul. We regularly attended the ‘Pardon de La Clarté’ in Perros, which was held in the little chapel of sculptured pink granite, where candles shone. The same chapel that the Comité Consultatif de Bretagne succeeded in rescuing, when later on the Germans wanted to destroy it for military reasons. From the ‘placitre, protected open place where the pardon was celebrated, a wonderful sea-horizon from Tregastel to the Sept Iles, was oncovered, bathed in sunlight and a kind of blue haze. The procession stretched out along the pathways behind the majesty of gold embroidered banners, reliquaries and sailor’s ex-votos, carried by women from Tregor in traditional costumes, with their best shawls and ‘coiffes’, to the sound of hymns in honour of ‘Itron Varia ar Skelder’ – ‘Notre Dame de la Clarté’, and Santez Anna. At nightfall the pilgrims gathered before the ‘tantad’, whose bright flames, stirred by the sea breeze, rose up against a navy blue sky already studded with stars.

In Guingamp, the ‘Pardon de Notre Dame de Bon Secours’, celebrated in July, was of a splendour beyond compare. The black Virgin, with a golden crown and robe studded with precious stones, was carried around the town on men’s shoulders. During the ceremony, the nave of the basilica was a sea of white ‘coiffes’. At nightfall, the procession wound its way through the main streets, which had been banned to traffic. Most of the participants held lighted candles, and it seemed as if the stars had fallen to earth, forming an immense luminous serpent, with religious songs and Breton hymns rising from it. The ‘tantad’ were erected at each corner of the triangle forming the La place du Centre. The priest lit them before the procession entered the church. I was completely immersed in the fervour of a people I identified with.

In Evran, I was sometimes at the Bas-Breil on a ‘jour de buée’. The washing was seldom done more than once a month, and sometimes less, as it had to be a sunny day, and only if the piles of sheets and linen in the spacious cupboards were running low. The women first did the washing at the ‘douet’, public washing area, then brought it back still wet in their wheelbarrows. It then had to be boiled in huge cauldrons over a wood fire.

It was then wrung out by hand: two people were needed to do the sheets, each holding one end and twisting in the other direction. It was then all laid out to dry on the gorse. In those days, cloth was strong and resistant to thorns. From afar, it looked as though large flower-beds of white flowers had suddenly blossomed, and replaced the gold of the gorse, or green of the grass-banks. Boiled and dried in this way, the washing was sparkling white, with such a fresh scent that our modern machines with their noxious detergents could never achieve. I sometimes also attended a pig-slaughtering. The cuts of pork were salted and preserved in huge stoneware jars. The large living-room was transformed into a make-shift factory, making sausages and black pudding with blood and intestines of the pork, which had been thoroughly washed and boiled. The metres of sausages were hung up for smoking in the big chimney, where several men could stand. Smoked sausages and fresh butter, which was salted and shaped as it came out of the churn, have remained in my memory as veritable treats associated with my visits to the Bas-Breil.

The feast of St.Barbe, whose little chapel was built on land given to the church by grand-pére Quéré, usually called us back to Callac towards the end of July, once we were of an age to take part in the dances organised in the big hall of the covered market. It was one of the rare occasions we had of meeting most of the numerous cousins, descendants as we were of ‘grande grand-mére’. The merry-go-rounds and fair stalls were set up in the square. The horse racing was held in a field, in Kerret, on the road to Morlaix. Callac was thus the stage of my first feminine encounters, my first flirts with the numerous daughters of a doctor from the town, and some others. The celebrations were hardly of a religious nature: they were purely secular, occasions for rejoicing and encounters for all the youth of the area, and that of our parents before us. The relative austerity and regularity of everyday life hardly permitted this, normally. ‘Discos’ and Saturday night dances had not arrived on the scene yet. Thus for the few days they lasted, they broke the rigid social constraints that remained, up to the Second World War, much stronger than they are today. It was virtually impossible to meet ‘girls’ too often without setting the whole town talking: fortunately the countryside was vast, with its welcoming woods and pathways and fragrant glens. At the time when I began to participate in the Callac celebrations, the dances of our grandmothers were still being danced there – quadrilles, polkas, waltzes, gallops and mazurkas. Our generation was soon to upset the traditions – we preferred the more modern and closer dances, tangos, foxtrots, charlestons and passo dobles began to replace the more classic dances. The ‘fest noz’ had not as yet put Breton dances back in fashion: at the time they were only practiced at a few rare feasts, such as that of Saint Loup in Guingamp, where they had become hardly more than objects of folklore. We knew where the electricity switches were: towards the end of the evening, we took it in turns several times to plunge the hall into total darkness for a few moments, which afforded us the opportunity of taking some innocent liberties with our partners. In Callac as in Evran, there were the visits to neighbouring farms, to relatives, neighbours, farmers or friends: all followed the same unchanging rituals. The glass of cider or cup of coffee, the bread and butter or the ‘crepes’ were accepted, after first refusing several times. The mistress of the house then took out the glasses and bowls, the round loaves of bread and mounds of butter, decorated with designs done with a wooden spoon. She opened both doors of her linen cupboard, thus allowing one to establish the richness of its contents, and selected a fresh cloth. Then, although they certainly did not need it, she carefully wiped each glass and each bowl in your presence before placing them in front of you. All these movements were carried out with simplicity, but also with a nobility and majestic slowness: the gift of time must be savoured, and it is bad form to be in a hurry when receiving visitors or being received.

VIII

It was thanks to my grandmother’s presence in Guingamp that I was able to attend my first Breton congress: that of ‘Bleun Brug’, held in the town in 1925. I was amazed at the richness and beauty of the ceremonial costumes from different parts of Brittany, as until then I had only seen the Trégor costumes, and was carried away with enthusiasm on hearing the choirs, their singing awakening unknown echoes in me. I hovered around the groups in costumes, marvelling at the splendour of those from Basse Cornouaille, adorned with strange designs of gold, yellow and orange embroidered on the waistcoats, hats and aprons, together with the light ‘coiffes’ and shawls of Léon, Vannes and les Iles. I tried to catch a few words of Breton, not venturing to speak to the participants. I also attended a few study sessions. One devoted to Luzel, animated by a priest, of which all I retained was the affectation of his speech. The other, more political, whose subject I have forgotten, but during which I noticed the intervention of a tall thin young man and a young Flemish abbot, also that of a frail old man, who looked as though he might collapse under the weight of his years at any moment. I only found out ten or twelve years later, when they had become friends, that these were Olier Mordrel, Jean Marie Gantois and Francois Vallée. During the discussions, France, its politics of linguistic assimilation, its government and its administration were not spared. Before dispersing, we had sung the Bro Goz Ma Zadou. I felt as though I had attended a meeting of conspirators, and began to ask myself countless questions. Brittany had been independent – there were still Bretons around who regretted that it was no longer so – one could fight for it to be so again! My thoughts opened up a whole new world.

From then onwards, I began to read all the Breton books I could lay my hands on. I replaced Alexander Dumas with Paul Feval, the history of France with that of Brittany. I purchased ‘La langue bretonne en quarante lecon’, the Breton language in 40 lessons, by Francois Vallée. It was then that I discovered Anatole Le Braz, Brizeux, Souvestre, Charles Le Goffic, and was aroused by the poems of the ‘Barzaz Breizh’. I had also discovered, amongst old papers in grandmother’s attic, Auguste Liégard’s manuscript notes on the history of Brittany, as well as a copy, without its binding, of ‘Etats de Bretagne’ by A. De Carne. Reading the latter, with the speech it reproduced, which Abbé Maury had delivered to the ‘Assemblé Constituante’, after that assembly had unilaterally repudiated the Franco-Breton treaty of 1532. This was for me another revelation. For centuries the Bretons had fought, first for their independence, then for their autonomy within the French kingdom. This history of my country fascinated me. I could hear the clash of battle, the cheering of the conquerors and moans of the defeated. I lived the obscure intrigues and shadowy conspiracies, shared the rejoicing of victories, the bitterness of defeat and treachery. And always, during every period, there was the background of efforts and conflicts of these people who were mine, who wanted to live and assert themselves in the community of nations. Why not continue, in our day, a fight that seemed to me as justified as it was necessary? Brittany was not dead. Its language, national consciousness, particularity, traditions, its own way of living, believing, thinking, its differences, all existed. I felt it deeply, together with the irresistible call of ‘La Patrie’, the Homeland.

During the years following on my baccalaureate, I began to connect more with Breton politics. I subscribed to ‘Breiz-Atao’: I took an interest in the trial undertaken by the government at the time, of Alsatian autonomists, was indignant at the police harassment of Breton autonomists following on the Chateaulin Congress in 1928, and in particular, continued to thoroughly investigate ‘the Breton subject’, with particular emphasis on the history.

I probably would have studied medicine, being such a well established tradition on my mother’s side of the family, if my Uncle Henri Liégard had encouraged me to do so. After much hesitation, however, I decided to register with the Law faculty, and the School of Political Science, whose courses appealed to me. It was possible to follow them from Clermomt, as it was only an hour from Paris. Consequently I acquired a season ticket on the northern network. I regularly made this journey over the following years, three or four times a week, both from Clermont and Compiégne, where my father was appointed Receiver of Revenues in 1928.

At the time, in reality I had no precise vocation. I found it intolerable to think of a life mapped out in advance, and at the mercy of a choice I had to make then, narrowing the horizons and possibilities that I wanted to keep as vast and open as possible. From an early stage, I had found it difficult to think of a future profession or career in purely material terms. I refused to be locked, in every sense of the word, into prospects impossible or difficult to change later on. Neither did I have any definite ambition. I preferred to keep the world open before me, as at a crossroads where one stops at length before finding ones way. It is just as well from that point of view that in the course of my life, events often determined the choice for me!