CHAPTER II

LE COMITÉ CONSULTATIF DE BRETAGNE

I

The declarations Jean Quenette made to the press as soon as he arrived were a breath of fresh air which I publicly supported in our paper La Bretagne. A prefet of the Empire or of any one of our republics had never before been known to publicly declare to the Bretons that he had come to Rennes “with the intention of giving you back all your rights and freedom possible, taking into account that these should not be contrary to present demands.”Maurice de La Gatinais who had probably consulted the new regional prefet on the text for any press releases, went even further: “I was chosen by the government, “he declared, “in my capacity as a Breton and, even better, as a Breton militant. Like M. Quenette, our new regional prefet, I consider that the Breton problem must be solved and I will render him my full cooperation to assist him in giving the Bretons back as many of their rights as possible.”

Many could not believe their ears, or their eyes! – The sails must be hoisted to catch this new wind of change! I made a point of doing so and paid a visit to Jean Quenette, without delay. His nomination and his words struck me as being the first consequences of the efforts I had deployed in favour of change.

Tall, strong, and solid as a rugby forward, the new regional prefet had a certain presence which was very striking. The man of politics behind the senior civil servant was immediately evident in his remarks. The former made one forget about the latter. He had a broader horizon and a freer spirit with a less narrow-minded outlook and a more independent spirit. He considered his mission to be one of governing rather than administration : he had obtained certain prerogatives over and above those of a mere prefecture civil servant , powers that a conventional career civil servant would have hesitated to use through fear of being repudiated and committing political suicide.

Being a career lawyer, Jean Quenette had thoroughly studied his Breton project.

– “ What worries me, “ he told me, “ is how I am going to make the Bretons understand in concrete terms that my appointment to Rennes marks a new departure in government policies regarding Brittany. You know that I am at present engaged in extensive consultations with Breton personalities on this point: I have included some of my Parliamentary colleagues, or better to call them ex-colleagues, in these consultations and also representatives from the economic, social and cultural life of the country.”

– “The most spectacular measure you could take for the Bretons, “I told him, “would be to gather together under your authority a regional prefecture comprised of the five Breton departments and not just the four which you administer today. This could be done by maintaining Nantes’ true role as a capital, alongside that of Rennes, in the field of economics for example, in order to humour certain feelings in Nantes. The people of Nantes today must feel they have been snubbed by being placed under the control of Angers. And also has Maréchal Pétain not declared, both to the people of Rennes and to those of Nantes, in apparently contradictory remarks, that their city would be the future capital of Brittany.”

– “In addition,” I added, “though I know that your powers appear within the general framework of laws governing the whole French territory, it seems to me essential that you make your mark by approving the cultural claims of Brittany. The latter have been practically unanimous and it is incomprehensible that successive French governments have as yet refused to grant them. A number of measures we call for could be dealt with by statutory means, even by a simple ministerial or prefectural order, through a faster and simpler procedure than that of legislative means. The latter will always create problems if the same laws and regulations are applied everywhere, even though the situations are different.”

I explained to him, as an example, about the difficulties we came across as regards the actual teaching of Breton history and language in the schools, the rigid stance taken by the French Education Office and the French Ministry of Education on this matter. I repeated what I had already said, in substance, to prefet George and a few others.

– “It should be for the law and the regulations to adapt to the needs and interests of the citizen and not the other way around. It certainly seems to be elementary but in administrative practices it is not always how it happens.”

As a Parliamentary Deputy and Lawyer, Jean Quenette had himself already had occasion to deal with the rigidity of administrative structures: he understood straightaway my thinking on this.

– “As regards Nantes, “he told me, “it does not depend on me alone: it would require a government decision taken at State level. I will try and convince the government: but I will surely come up against my colleague in Angers. But, it should be possible to do something as regards the cultural claims. I will inquire further but will need some precise documentation.”

“Why not, “I replied, “have this cultural documentation drawn up and examined by a special body you could call on to sit in with you and who could suggest concrete measures which could be taken at regional level? Representatives of regionalist and cultural organisations could be called on to take part in this special body. In order to justify the creation of this body you could bring up the fact that you thought it wise to call on a certain number of representatives from Breton opinion to sit alongside you, in order to provide a consistent and concrete foundation to the new provincial level. You would thus lay the groundwork for a regional administration which needs to be set up, and regional institutional bodies without which there can be no provinces or regions worthy of the name.”

Jean Quenette paused for a minute, looking thoughtfully towards the gate of the prefecture, the central courtyard and the little square nearby. The suggestion seemed to appeal to him.

“I need to think about it,” he told me, “I will discuss it and if necessary make a plan. Come back and see me in a couple of weeks and, in the meantime, keep in touch.”

I saw Quenette again several times after that to finalise the project which culminated in the forming of the Comité Consultatif de Bretagne. The first stage was a restricted meeting organised by the Government which Guébriant and Jean Quenette agreed could be held in Landerneau at the beginning of July 1942, at the Head Office of the Agricultural Trade Union. Apart from Guébriant and myself, those who attended were Jean Crouan, the deputy mayor of Quéménéven, Commander de Rodellec du Portzic, ex navy officer who had become mayor of his commune and who was one of the management councillors of the Agricultural Trade Union . I provided them with all the explanations they required on the policy I pursued, which differed fundamentally from that of “L’Heure Bretonne” and that of the P.N.B.; different in the sense that it maintained the solution to the Breton question had to be considered within the framework of French unity, thanks to the reforms promised by Maréchal Pétain. I also furnished them with all the necessary information regarding the circumstances surrounding the establishment of “La Bretagne” and of the events which , under our management, had prompted the new political orientation I had given to “La Dépêche de Brest” , after the departure of Le Gorgeu . This Breton press that I was responsible for with its Breton spirit that had become more powerful after these events , was a force to be reckoned with, and had to be used in favour of the measures and reforms we wanted to obtain . We agreed on the need to match the good will showed by Jean Quenette and the Vichy government. I suggested that a precise program and official minutes be drawn up. De Guébriant himself insisted on carefully going over the minutes. We therefore suggested the creation of an official “Provincial council”, based with the regional prefet, and composed of people chosen for their knowledge of Breton matters and for their social and geographical representation from all over Brittany. We also evoked the fundamental claims already submitted to the government in various documents: Breton unity, a provincial council and the teaching of Breton for which we suggested the creation of special teaching courses and of a commission based with the Chief Education Officer advising him on the choice of textbooks, methods to be used etc… This all matched my fundamental beliefs. There was no point obtaining concessions on paper, if it was not possible to supervise their application in the field.

I knew that the support of Guébriant, whose advice was highly considered by Maréchal Pétain and his entourage, was an essential factor in the success of our project, and was also a decisive factor encouraging Jean Quenette to pave the way for them to be carried out. It was already important that the government, directed by Pierre Laval, had given the latter certain prerogatives in matters concerning the settlement of the Breton question: but he also needed to feel that he had the support and encouragement of the province’s important personalities in this matter. But, he was not lacking in advice to the contrary: he told us quite frankly, when a few months later he set up the Comité Consultatif de Bretagne. Some kind souls, Breton or not and some notables from former political circles in disrepute, were warning him that he would “fall into a trap and urged him not to take action”. I was personally already the object of violent attacks in anonymous lampoons being unofficially circulated. Since we were gradually moving towards some tangible and concrete achievements, some Breton anti-bretons were having a field day in the guise of a French patriotism, easily exploited in times of war. But I knew that many defeats and setbacks throughout our history stemmed from quarrels and rifts stirred up by the French seat of power throughout the ages, alas even from the betrayal of certain Bretons, even though they were often considered as some of the most prominent from amongst their people and their nation. That tradition certainly had not died out and it would have been surprising if it had not appeared again: but it would have taken far more than that to discourage me! On this score as on many others, history repeats itself.

I had brought the minutes of the meeting in Landerneau to Jean Quenette and discussed them with him. He followed up on them without delay: He called a number of Breton personalities, with whom he had already discussed, to a meeting for the 12th of August at the regional prefecture. The purpose of that meeting was to “examine Brittany’s requirements and the means of fulfilling them”, which was what I wrote in a note I sent to the regional prefet and all the participants the next day, together with the minutes.

This note also listed the names of the participants in alphabetical order, together with the occupation and responsibilities of each one : Jean des Cognets , André Dezarrois , R. de L’Estourbeillon , Yann Fouéré , Maurice de La Gatinais , Roger Grand , Budes de Guébriant , Edouard Guéguen , Edgar de Kergariou and Abbé Mary . These ten people, through the diversity in their origins, their activities and their occupations, in fact represented a very broad range of Breton opinion at the time. There were three parliamentarians or ex parliamentarians, two personalities from Loire Atlantique, two representatives from the field of business and two from the press , one from the church, two from University circles, three from the Breton movement , two local mayors and finally two of Maréchal Pétain’s national councillors.

Each in turn, the participants gave a quick exposé on the subject for the meeting. An overall agreement on the essential points quickly became apparent from our discussions. Jean Quenette made a decision on the spot to incorporate into the teacher training school curriculum, an optional Breton language course in the program for the Breton Civil Service Exams: he also immediately decided to create a Breton teachers’ training Institute, organised and financed by the region. This would allow them to make use of their capability to teach Breton to their pupils within the framework of the Carcopino ministerial order of the 24th December 1941, rounded off by that of Abel Bonnard of the 18th June 1942. The latter had decided to grant an allowance to teachers, who would start up classes on “local dialects “in their schools. Finally , he promised to study the possibility of forming an official “ Provincial Council “ , for which he preferred to obtain the approval of the government beforehand.

– “This approval “, he told us, “will undoubtedly be given, in view of the conversations I have already had in Vichy and in Paris regarding this matter. “

It was thus decided that I should submit a type of minimum program in writing, to the large regionalist and cultural associations, in order to have their formal approval to the policies being considered following on the exchange of views that had just taken place. Finally it was decided that later on, at the request of the regional prefet, I should convene the delegates who had been nominated, limited to two per association, by those large regionalist and cultural organisations who had declared their approval of this minimum program. The object of this meeting, to be presided over by the regional prefet at the Rennes prefecture, was to discuss Breton cultural problems and to gather suggestions from the participants as to how these could be resolved.

All the associations and organisations that I had contacted on behalf of the regional prefet sent a favourable reply, with the exception of la Fédération Regionalist de Bretagne run by Jean Choleau in theory, but which had long since ceased to show any signs of activity, apart from their perseverance and regularity in the publishing of their review “Le Réveil Breton”. Afterwards this was seen by some as the sign of an intentional abstention on the part of Jean Choleau. In fact, he wrote to me that he felt the regional prefet himself should have advised him of his projects and then convened him personally. I told Jean Quenette about this little display of hurt vanity.

– “This reveals neither much intelligence nor much openness of mind politically,” he told me, “You should just drop him. We can do without him especially as you seem to have all the regional and cultural associations. I will chase up Jean Choleau myself at a later stage.”

Jean Quenette had been very impressed by the display of Breton unity and fervour at the triumphal Bleun Brug held in Tréguier around Father Perrot in August. The congress had been symbolically organised to honour the memory of Duke Jean V and to pay homage to this great Breton sovereign, who had known , not only how to maintain peace in his country, but also to give it a prosperity which was the envy of all his neighbours. The French and English dynasties at the time were constantly at war, fighting over the territories from Normandy to Guyenne and Bourgogne which would determine the shape and fate of France. All of militant Brittany had come together at the Tréguier Bleun Brug, gathered together as a brotherhood, in the centre of this paved town, with the Breton colours and the enthusiastic crowd filling the air with Breton songs and hymns. An official banquet had assembled around the life and soul of Bleun Brug, who was a revered personality for all of us, the Senator-Mayor of the town, Gustave de Kerguézec, who previously had been chosen by the “blues” or republicans against the “clericals”, also Canon Brochen who was vicar-general of the diocese of St.Brieuc as well as the sous-prefet of Lannion. In the speech I was called upon to give I hailed the official presence of the latter, emphasising the new era that it appeared to introduce in relations between Brittany and the central power. I managed to link together in the same tribute Tréguier’s two famous Bretons, Saint Yves and Ernest Renan, united beyond their differences of opinion, of life and of faith, in their love and defence of Brittany, their common country. Canon Brochen, who had been a little apprehensive, did not turn a hair, and de Kerguézec who had once been called the red viscount, was eager to show his approval of my words. He cornered me at the end of the banquet and whispered in my ear:

– “Your speech! Wonderful! You are a magician: it was dangerous ground: but we are in a time when there must be reconciliation and old passions must be surpassed. The ideal meeting ground is in the service of Brittany. On this score I am wholeheartedly behind you. “

This event probably prompted Jean Quenette to hold the first meeting of the personalities he had assembled, on the day following the jubilee of R. de L’Estourbeillon, which was to be held in Rennes on the 11th of October 1942 and was organised by L’Union Regionalist Bretonne to celebrate the 40th anniversary of his election to the presidency of that association. All of militant Brittany would be assembled there again, all the factions united together to pay tribute to one of the pioneers of the struggle.

– “I will not be able on this occasion to announce , as I would have liked to do, the entry of the Loire Inferieure into the region of Brittany,” Jean Quenette had told me . In spite of my efforts, I have made no progress on this point. It seems that within the circles of the Nantes Chamber of Commerce and Industry they are violently opposed to it, even though I had offered to set up the headquarters of the Regional Economic Administration in Nantes. In Vichy the matter is only considered of secondary importance. Even though I had an irrefutable case and had obtained the approval of my colleague Dupard, prefet of Loire-Atlantique. At least, in my official capacity, I will be in attendance on Sunday morning at the solemn Mass which is to be celebrated in Rennes cathedral for the jubilee of M. de L’Estourbeillon. I have insured that the archbishop of Rennes, Monsignor Roques, will preside in person. I will also attend the ceremony paying tribute to M. de L’Estourbeillon in the afternoon at the Rennes Theatre, and on behalf of the government, will publicly announce the creation of our committee. I want my presence to be a sanction and a spectacular demonstration of the government’s interest in Brittany and their satisfaction of its legitimate claims. “

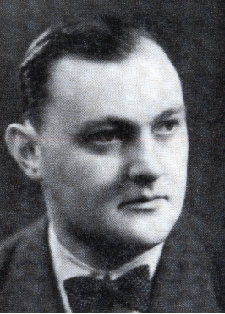

Marquis R. de L’Estourbeillon.

Marquis R. de L’Estourbeillon.

II

When the States of Brittanny assembled long ago in one or other of our towns, a solemn High Mass would mark the opening of their deliberations. The High Mass celebrated in Rennes cathedral on Sunday 11th October 1942 was irresistibly reminiscent of this. The cathedral was full to capacity and the crowd spilled out into the square with a flood of sound from the church bells sweeping over them. The sun was also present and the weather was mild. The future members of The Comité Consultatif de Bretagne, all present, attended the ceremony, behind the Regional Authorities whom the Prefet had gathered around him. In accordance with the Republic’s official protocol, Monsignor Roques, Archbishop of Rennes, Primate of Brittany, had come forward to welcome the Regional Prefet at the entrance of the cathedral. He had accompanied him to his seat near the choir. Father Perrot, feeling rather out of place in these solemn surroundings , so different from that of the country churches where he felt more at ease, had gone up onto the rostrum and delivered a homily in Breton and in French , symbolically associating both languages of the country.

1942: Yann Fouéré and A. Dezarrois, leaving l’Hotel de France in Rennes, on the occasion of the ‘Jubilé Breton’ for the Marquis R. de l’Estourbeillon.

1942: Yann Fouéré and A. Dezarrois, leaving l’Hotel de France in Rennes, on the occasion of the ‘Jubilé Breton’ for the Marquis R. de l’Estourbeillon.

In the afternoon, after the friendly banquet at the Hotel de France which had brought together the main leaders of the Breton regionalist, nationalist, political and cultural organisations around de L’Estourbeillon, we found the Rennes Theatre already crowded. During the show, with the Rennes Celtic Circle taking part, a messenger from Raymond Delaporte came to me to point out that a number of Breton nationalists, members of the P.N.B., were present in the hall and that considering the Regional prefet’s presence in an official capacity, the singing of the Marseillaise would follow that of the Bro-Goz, which could provoke some incidents. I had been warned already that a certain number of the P.N.B. militants, the most active ones, took a dim view of the creation of the Comité Consultatif, as it did not include any official representative from the P.N.B. They saw it in practically the same light as did Jean Choleau, as an attempt by the French authorities to “manipulate” the Breton movement. A logical assumption to all appearances, and one which could stand up to argument but which did not take into account the fact that a systematic opposition, though it can often act as an incentive, must guard against purely negative and non-productive attitudes that could get in the way of an essentially pragmatic policy, such as the one we proposed to follow. Raymond Delaporte understood this very well, but had to take into account the state of mind of his troops.

I had also been warned a few weeks earlier that the German authorities were beginning to worry about the political activity resulting from our meetings and interviews with the Regional Prefet, for whom they had no particular regard. They had been hypocritically warned by some that this political activity taking place both at the Regional Prefecture and the Regional Delegation for the Youth could, at some stage, be the cause of public disturbance. Oddly enough, many years later, after the creation of the M.O.B. in 1957, this was the same reason given by the prefets of Rennes and Nantes for prohibiting conferences which I was to hold in both those towns!

The posters done by Le Gatinais called for a gathering of the Breton youth under the aegis of Marechal Petain. They showed a young Breton, wearing a kind of uniform with ermine coat of arms. This association of Breton activism with representatives of Vichy in Brittany, caused the German security forces some anxiety. All those in Brittany, whether ‘resistants’ or not, who went against the goals they felt were within their reach, were obviously fanning the flames. In addition, I learnt much later that the German police services had an informer in the prefecture, well placed in spite of his modest functions. I felt it was safer to foresee possible reactions from them. A few weeks earlier, the Breton Youth meeting organised by the Regional Youth Delegation which was to have been held in Josselin, from the 18th to 21st September, had been banned by the occupation forces. I discussed it with some of my colleagues from Kuzul Meur: they advised me to call on Hans Grimm, from Alsace, who was in charge of political affairs for the German Security Services. The latter, at the time, had set up offices in the small building that had previously been a University Hall of Residence near the Saint Vincent Hospital and Clinic. I found Grimm to be relatively open, in spite of his function. The fact that he was from Alsace enabled him to understand perfectly our political problems and situation. In addition, he knew Hermann Bickler who had become an important figure in the German Army Services. He indicated that he would see to it that the services of the Occupation Forces are more precisely informed of our stand, and that if the Breton Youth gathering had been banned, it had been because the authorities wanted to avoid any mass demonstration that could be an easy prey for troublemakers.

– “Your meetings in the Rennes Theatre or at the prefecture are private ones which can not be confused with the planned Breton Youth gathering, “he told me.

Nonetheless, if the Marseillaise rang out in the Rennes Theatre, it could easily be decried as a provocation and be the cause of some incidents, even apart from those that Raymond Delaporte feared. Some hearty souls would surely have jumped on the opportunity! As for myself, I held no greater liking for the Marseillaise than the P.N.B. members. Too many Bretons had already and, sadly, would again be massacred on behalf of that warrior song.

Thus it was that I decided that evening to go and speak to the Regional Prefet in his Theatre Box. I explained to him that it was not customary, at the end of Breton meetings, to sing any other song but the Bro Goz , for which the assembly would stand , and that the singing of the Marseillaise, or any other national or partisan song would inevitably result in transforming today’s demonstration of unity into an inappropriate political demonstration capable of creating incidents.

– “As a native of Lorraine, I would have preferred that both the Marseillaise and the Bro Goz be sung. But as Regional Prefet of Brittany I have no objection to standing and listening to the Breton National Anthem…” he assured me.

At the end of the meeting, Jean Quenette took his place on the stage, surrounded by the principal members of the committee being created. He officially announced its creation which was greeted by hearty applause. Then sharing in the tributes that had been made to R. de L’Estourbeillon throughout the day, he officially awarded him the Francesque medal on behalf of the Head of State, Maréchal Pétain .

This did not have the desired effect and triggered off the inevitable incident, though undoubtedly on a lesser scale than it would have been with the singing of the Marseillaise. “Down with France” began shouting Vissault de Coëtlogon, from one of the top rows in the theatre. There was a great hubbub as the police evicted Guy Vissault , and also Job Jafré, the editor of “ L’Heure Bretonne “ who had attempted to restore calm . The ceremony was only briefly disturbed. The Bro Goz was sung in peace and quiet.

Jean Quenette did not hold this incident against anyone, thus proving his political savvy. He had Guy Vissault brought to his office before releasing him. He had a cordial discussion with him regarding his motives. In spite of his youth, Vissault already possessed a strong personality:

– “He’s a great guy, “he kept on repeating as he emerged from the prefet’s office, a free man. “ If only all Frenchmen were like that, we could eventually get on together!”

As for R. de L’Estourbeillon , he could not care less about the Francesque: he already had numerous decorations , including the Légion d’Honneur and the Croix de Guerre. He accepted it but always refused to wear it.

1942: On the stage at the Théatre de Rennes during the Marquis de L’Estourbeillon’s speech. In the front row, MM. Dezarois, Feschotte, Quenette, the other préfets hidden – 2nd row MM. Touros-Mercier, Fouéré, Jaigu, Guéguen, Jaffrenou and Le Berre.

1942: On the stage at the Théatre de Rennes during the Marquis de L’Estourbeillon’s speech. In the front row, MM. Dezarois, Feschotte, Quenette, the other préfets hidden – 2nd row MM. Touros-Mercier, Fouéré, Jaigu, Guéguen, Jaffrenou and Le Berre.

On Monday 12th October, the Breton personalities that the Prefet and I had convened, did indeed meet together at the Rennes Prefecture, in the county council’s large meeting hall, with Jean Quenette presiding. He had asked R. de L’Estourbeillon to take the seat on his right: on his left was Prosper Jardin, president of the Guillaume Budé association, a very knowledgeable man, being a legal expert, a Latin scholar, a scientist and in charge of one of the big pharmacies in Rennes. He had been specifically chosen because he did not belong to the civil service, explained Jean Quenette , to take on the role of General Secretary of the organisation we were creating . Jardin would coordinate, in liaison with him, all the administrative tasks and activities that this involved.

– “I want to emphasise ,” he continued,” that I decided to create this organisation on my own responsibility but with the complete agreement of the government . Brittany will be the only province, for the moment at least, to benefit from this measure. The government recognises that it has specific needs and interests to be addressed and should be supported and protected on the whole, above and beyond the administrations and departmental divisions that are really the only existing structures at present.”

We all listened attentively: surprise mixed with disbelief could be read on the faces of some of my colleagues. It was certainly the first time that a Prefet had officially come out with such words. Could there still be some Frenchmen who remembered that Brittany was not just a holiday location or a Folklore reserve? Alongside the older Breton militants in the hall, the true pioneers of our struggle, it was a pleasure to recognise the faces of those who represented the younger generation like me. There were Taldir and Francis Even who represented the Gorsedd, Roger Grand and Léon Le Berre, the Breton Association, Father Perrot and James Bouillé , the Bleun Brug, L’Estourbeillon and Sulian Colin, the U.R.B., Professor Guéguen and Madame Galbrun, the only woman on the Comité, representing the Fédération des Cercles Celtiques. René Daniel and myself represented Ar Brezoneg er Skol, whilst Martray represented L’Union Folklorique de Bretagne, Pierre Mocaër and Florian Le Roy, L’Institut Celtique created a few months beforehand. Also present were Budes de Guébriant , Edgar de Kergariou, Jean des Cognets, Father Mary, André Dezarrois, Inspector of the National Art College, who had been personally called by the Prefet to be a part of the new organisation . Oddly enough these were the “qualified personalities” appointed in their official capacities by the Government, who were called at a later stage to sit on the Regional Council of Brittany after the regional reform of 1972.

After Jean Quenette had addressed the meeting, there was a general discussion regarding the name that should be given to the new organisation, the name by which it would be referred to officially and that would be communicated to the Government and the press. Cultural Council was suggested by some, as its activities would be mainly in this field. I felt this was somewhat restrictive: It seemed to me that we might be called on to overlap in other fields. We finally agreed on Comité Consultatif de Bretagne. This had the advantage of both marking the limits within which our authority lay and not restricting beforehand the extent to which we might be called on to take action. It was also agreed to form a number of commissions, divided between the members of the committee. One for Breton language and education that I was to report on, one for Breton History with Léon Le Berre as reporter, the Fine Arts one was allocated to André Dezarrois and Folklore to Florian Le Roy, with lastly a general one to Pierre Mocaër. I knew the latter was fully in agreement with me on the necessity of extending our field of action beyond that of Culture and Fine Arts.

I also requested and obtained the setting up of a Standing Commission, composed of the reporters from the various Commissions who would meet more frequently and, in between the Committee’s Plenary Sessions, would be in charge together with the General-Secretary of following through on any decisions made. It would be given the responsibility on a permanent basis of representing the Comité Consultatif at the Regional Prefecture as well as the various other Administrative Services of the region.

I felt very strongly about this. A constituent body, be it elected or not, is a nothing if it does not have the efficient means of pursuing and controlling the implementation of the decisions taken and recommendations made. This applies even more so in the case of an advisory body. The Comité ought not to exist purely as a sort of tapestry or just as an organisation to impress: little by little, it should take on specific functions. It should really make its presence felt in Brittany’s affairs. It was just the first stone on which true regional institutions could be built and which the future would specify. We had only taken the first step today. In a similar manner the States of Brittany’s intermediary commission had mainly succeeded in keeping alive Breton autonomy, in the face of royal authority. And really, were we not just carrying on from them? The circumstances and times were certainly different. But this did not in any way alter the fundamental continuity of the struggle we were involved in to ensure that the Breton people’s identity be maintained and their interests defended, and also Brittany’s collective and institutional freedom that was necessary for its survival and for the control of its destiny once more. For the first time since its autonomy was taken away, in spite of the Breton’s protests and rebellion, Brittany, through the creation of the Comité Consultatif with an official representative of the French Government was once more represented in its own right. The establishment would be worth what the men, who had taken on the task of motivating it, were worth.

1943: Official photo of the Comité Consultatif de Bretagne meeting at the Chateau de Josselin.

1943: Official photo of the Comité Consultatif de Bretagne meeting at the Chateau de Josselin.

It is well known that from the time the Comité Consultatif was created, a number of concessions were made and concrete results obtained, mainly of a cultural nature. I saw to the efficient running of the Standing Committee. I always kept in mind the necessity of closely supervising the practical application of the measures we advocated and the decisions we requested the Regional Prefecture to take in order to put them into practice. Thus it was that the Standing Committee and the Comité became accustomed to calling on and listening to a number of regional senior civil servants or their representatives : in particular the Head of Educational Authorities and sometimes the Economic Affairs Administrator. In fact, the Prefet had requested that the Head of Educational Authorities, the Regional Youth Delegate and the Chief Architect of Historical Monuments regularly attend, in their official capacities, the plenary sessions of the Comité.

It was naturally with the Head of Educational Authorities, Souriau , that we dealt with most . He was a cold phlegmatic person. He always remained unruffled and never lost his self-control. Our dealings with him were always marked by extreme politeness and courtesy as was proper. Frequently though, one could sense an obstinate resistance in the background, coming from an administration bogged down by routine, resistant to change, which obeyed certain specifically restricted dogmas, and who looked on uniformity as a rule which could not be broken. Adapting those rules for Brittany and to the decisions which the Regional Prefecture might take, within the limits of his authority, obviously involved changing those dogmas. It involved the introduction of the basic principles of diversity, contrary to the firm’s way of thinking, which could only complicate and increase the tasks whose elaboration down to the smallest detail came from Paris.

Whenever conflicts became too acute or differences of opinion too intense, I always had the option of appealing directly to Central Administration. I had the good fortune of having there an important source of influence in my friend, Jean Mouraille, who had become principal Private Secretary to Abel Bonnard, a member of the French Academy and the National Education Minister. Neither his Minister nor he were conventional personalities: neither of them belonged to the administration they were supposed to represent. They looked at it mainly from the outside. Of course, my personal relationship with Jean Mouraille was well known at the Education Office and this made it much easier to settle many matters without a word being said. It is always possible to come to an understanding with people who have the right connections, and what is left unsaid but is given to understand is often more important than what is said.

This is not to say that there were no sharp clashes at times. Souriau and I clashed with each other on several occasions, in spite of the necessary courtesy. When Abel Bonnard agreed that an optional Breton exam for the primary school certificate be established, Souriau had simply passed on this decision to the civil servants under his orders, without any instructions or directions as to how it should be implemented. We had suggested the establishment of oral and written exams with translation, and had requested that a competent travelling examiner be sent to the exam centres to assist the examiners in charge of setting up the exams for the primary certificate. We knew from past experience of the latter’s incompetence in matters relating to the Breton language. But Souriau would not hear of it and refused to add anything to his circular: plainly the best way of shelving the policy of reform that the Ministry had decided on!

I notified Jean Mouraille. André Dezarrois, for his part, interceded at length with Abel Bonnard who was the Fine-Arts Minister and whom he knew well:

– “If I understand correctly,” he finally said, “I need to get rid of that Head of Educational Authorities for you. But Who? I have no suitable person at hand… “

III

Whilst André Dezarrois, in charge of the Fine-Arts commission, had embarked on a relentless struggle against the French Administration and the demands of the German Army, in defence of our bronze statues as well as our historical monuments and urban planning, our first concern was to deal with the manner in which Breton History was taught in primary schools. In 1941, we had obtained agreement that an exam in Breton History should be compulsory for the primary school leaving certificate. But there were no Breton History textbooks that the Administration could suggest the teachers should use. Those that had been used before had long since run out. The private schools were better off, with Raison du Cleuziou’s textbooks at their disposal. It was out of the question that we be permitted to distribute “La Petite Histoire de Bretagne” by C. Danio, published by the P.N.B., guilty of “looking at Breton History solely through Breton eyes.” Professor Armand Rébillon was preparing a school textbook: but we knew that he looked on Breton History “solely through French eyes”. René Daniel, A.Le Lannou and I decided to write one; but it was a time consuming exercise that was foiled by events.

Teachers were therefore more or less on their own and we decided that the most effective way was to establish a competition between the schools. A prize was awarded for the best paper submitted by the schools that had set Breton History exams for the primary school leaving certificate. The papers we subsequently received amply demonstrated that as regards Breton History the primary school inspectors, responsible for Brittany, knew far less than the pupils whose papers they were correcting: one of them was even surprised that the pupils had referred to Nominoë and other Breton kings, who he peremptorily asserted were a figment of their imagination!

We had also rapidly obtained practical new measures for the teaching of Breton. The compulsory Breton classes , authorised and financed by the 24th of December 1941 Carcopino ministerial order , and the 1st of June 1942 one of Abel Bonnard , were extended to the Rennes and Nantes Vocational Training Institutes that had taken over from the Teachers Training Colleges. We took advantage of the situation to request that this be extended to the Secondary Schools and that a Breton language exam should be formulated for the Baccalaureat, as teachers at the time were obliged to pass through this general preparation. On 1st December 1943, Abel Bonnard issued another ministerial order that finally established an optional Breton language exam for the Primary School Leaving Certificate. And, since the arrival of Jean Quenette, a Breton Language paper was included in the decentralised exams for the posts of civil servants in the Prefecture, for town clerks and for members of the police force of the three departments where Breton was widely spoken.

We were at least better prepared as regards the teaching of the Breton language, thanks to the prior efforts of Ar Falz and Ar Brezhoneg er Skol, and not as lacking in resources as for the teaching of Breton History. We had not waited for the creation of the Comité Consultatif to avail ourselves of the facilities approved by the Carcopino and Abel Bonnard ministerial orders. I had again used a policy of incentives, encouragement and financial assistance for Breton classes, within a framework of organised spare-time activities, in accordance with decisions already obtained from the National Ministry of Education shortly before the war. When we had subsequently obtained the generalisation of these measures and the possibility of holding Breton language classes within normal school hours, we made sure we were organised to make full use of these new facilities. The burning question arose, not only of the textbooks but of the spelling system. Until then we had been able to manage with Francois Vallée and Roparz Hémon’s grammars and dictionaries, though they were really not designed for use by school children. In addition, the teaching of the Breton language had become an official subject and the Head of Educational Authorities would only accept the use of books and textbooks in the schools which had been approved by him. The matter was discussed by the Comité Consultatif.

Though the Christian Brother’s schools had the textbook , “Me a zesk brezoneg” by Uguen and V.Seité , printed for use in the private schools , I had the textbook , “Me a lenno” , prepared long ago by Yann Sohier , printed for use in the public schools . The Head of Educational Authorities refused to allow it to be distributed, finally disclosing that the preface contained “a sentence which held unacceptable political implications”. The phrase translated into French was as follows: “ Yann Sohier,” wrote Roparz Hémon ,“will continue, even beyond the grave, to inspire younger generations in their struggle, the struggle of the Celts finally aroused after centuries of shame and slavery.”

I persisted in enquiring if, aside from the preface, Yann Sohier’s text would meet with the Education Department’s approval. Souriau replied in the affirmative:

– “Very well then, if that is the case,” I replied, “I will have the page with the preface carefully removed from each book and we will bring you all of these copies that we plan to distribute amongst the schools. You will then be able to put the Education Department’s stamp on all of them so that there are no mistakes, thus making it easier for your inspectors to carry out their inspections.”

A few days later, all in one go, I brought over a thousand copies of “Me a lenno”,with their prefaces amputated, to the Education Department who, making the best of a bad job, conscientiously put their stamp on each and every one of them.

This is the reason why most of the copies of “Me a lenno” that can still be found from time to time in second-hand bookshops, have the Education Department’s stamp on them. Those that do not have it, and therefore still have their preface, are extremely rare.

These constant little fencing matches we had, mostly with the National Education services, taught me a great deal about the resistance from the Administration in general which the State’s highest authorities were up against. Though theoretically under their control the Administration, whenever it wished, placed obstacles hindering the implementation of decisions they made. In a country as hierarchical and centralised as France, the services, ministries and administration have become fortresses whose improvement has become virtually impossible. Every one of them is protected by all sorts of acquired prerogatives, financial privileges and statutory guarantees. These prerogatives, privileges and guarantees are in fact established solely for the purpose of supporting a new social class, those who have assumed exclusive rights to control the State. At the same time they control the lives of thousands of citizens who are used by them to vindicate their positions, whilst they are supposed to be at their service. Breton authorities will not get away from this vicious circle, without first knocking down this structure in order to rebuild it in accordance with more humane and liberal minded concepts, employing methods open to more modern and flexible ideas, therefore more efficient and realistic.

In order to control the application of decisions taken in favour of the teaching of Breton that, unlike the History of Brittany, was still optional, I virtually had to establish a parallel administration, thanks to Ar Brezoneg er Skol. Few teachers were competent to take on this new task. We distributed books and textbooks free of charge. In addition to Sohier’s book we also had “Yannig” printed, a reading book by A. Le Deuzet , and “Lommig” by Xavier Haas. We gave financial assistance to the teachers and organised Breton language competitions between the schools, in the same way that the Standing Committee had done for Breton History, with a prize. Alain Le Berre regularly visited the Breton classes inquiring as to the needs of each one and receiving the teachers’ comments. He had to use public transport or his bicycle, as neither our budget nor the increasingly strict petrol rationing permitted us to use any other means. For each class we tried to find a financial patron: failing that we supplemented the financing with gifts, subscriptions and the coffers of Ar Brezoneg er Skol.

The Comité Consultatif rapidly became aware of the fact that the most urgent matter was to prepare teachers for the new tasks they were being asked to perform, as much in Breton History and Geography as in the teaching of Breton Language. We had discussed the matter with the Regional Préfet right from the beginning of our meetings. It was not a task that could be left in the hands of the only regional educational Institutes, newly formed and closely controlled by central administration in Paris and Vichy. These concerns gave birth to an initiative that could have had an invaluable future if the Liberation had not swept it away, being also the most original and the most useful one taken by the Regional Préfecture at the request of the Comité Consultatif. It entailed continuity ready to assert itself and we intended to make sure that it be respected.

1943: Inauguration at la Ville Goyat of the Auguste Brizeux College. From left to right, Florian Le Roy, Senator Roger Grand, schools inspector René Daniel , Joseph Martray, Yann Fouéré beside Mme Galbrun.

1943: Inauguration at la Ville Goyat of the Auguste Brizeux College. From left to right, Florian Le Roy, Senator Roger Grand, schools inspector René Daniel , Joseph Martray, Yann Fouéré beside Mme Galbrun.

The Auguste-Brizeux College, situated in la Ville-Goyat of Taupont, near Ploërmel, in a large old building specially converted by the Regional Préfecture, was destined to become a sort of Summer or Holiday College or University, where both primary and secondary school teachers and professors who wanted to improve their knowledge of Breton History and Geography and of the Breton Language, could be welcomed free of charge. They could thus improve their knowledge of a Breton Culture , increasingly important for them to have as our country’s education was bound to become “regionalised”, and thus better adapted to Breton needs and interests. This was the concrete goal we pursued. The College, being an out-of-university facility, depended solely on the Regional Préfecture which financed it. The Education Department no doubt looked on this facility, which evaded the centralised system’s standards of education, with some suspicion! Nonetheless the Head of Educational Authorities came along with Jean Quenette to officially inaugurate it on the 15th July 1943.

The morning of the inauguration, the Regional Préfet had called the Comité Consultatif to a plenary session at the Chateau de Josselin, the magnificent historical setting placed at their disposal by the Duchess of Rohan. The photograph taken on that occasion has appeared in a number of works, and is to my knowledge the only one that has most of the members of the Comité gathered around Jean Quenette, Souriau, the architect Cournon, the Duchess of Rohan and her son. Jean Quenette was fond of symbols and spectacular gestures he considered to be of a kind to stimulate the imagination. One of these gestures had been when, annoyed at not having succeeded in bringing Loire-Atlantique back into the bosom of the Regional Prefecture of Brittany, he had arranged to have not only the four Préfets of his region but also the Prefet of Loire-Atlantique accompany him during a pilgrimage to the Sainte-Anne d’Auray Breton war memorial. The meeting of the Comité Consultatif at the Chateau de Josselin was another one of those gestures.

1943: Inauguration of the A.Brizeux College – In the doorway (his back) Jean Quenette in conversation with Senateur Roger Grand et Chanoine Mary. On his right Yann Fouéré in conversation with the Prefet from Morbihan. In the forefront from left to right, Alain Le Berre, Professeur Gueguen, Francis Even, Taldir, Leon Le Berre(his back), on the right (his back) André Dezarrois in conversation with Joseph Martray and René Daniel.

1943: Inauguration of the A.Brizeux College – In the doorway (his back) Jean Quenette in conversation with Senateur Roger Grand et Chanoine Mary. On his right Yann Fouéré in conversation with the Prefet from Morbihan. In the forefront from left to right, Alain Le Berre, Professeur Gueguen, Francis Even, Taldir, Leon Le Berre(his back), on the right (his back) André Dezarrois in conversation with Joseph Martray and René Daniel.

The actual inauguration of the Auguste-Brizeux College, in La Ville-Goyat , took place in the afternoon. The Préfet, the Head of Educational Authorities and members of the Comité were received by the teaching staff and the first students. The primary school inspector, E.Coant, was the headmaster of the College and his wife was the efficient and dedicated bursar.

André Guilcher, who later on became a professor at the Sorbonne, shared the teaching of History and Geography with E.Coant , whilst Quentel and Robert Audic were specially in charge of the Breton language classes. The weekly teaching program was comprised of 12 hours of Breton Language, 6 hours of Geography and 6 of Breton History, with 3 hours dedicated to Breton and French Art and Literature. Finally 9 hours of Sport, Breton songs and dancing completed the program.

The setting was an ideal one and conducive to learning and creative studies. During the summer, with Alain Le Berre, I organised a debate on Ar Brezhoneg er Skol. Teachers and pupils were all one big family. I still remember young Madame Guilcher going down to the water’s edge to wash her clothes just like the washer-women in the old days did. La Ville-Goyat was surrounded by peaceful countryside, resplendent and warm under the summer sunshine. Golden fields of wheat mingled with green pastures. A large pond nearby, its shores cluttered with reeds and water-lilies, was a source of coolness. Sometimes classes were held outside under the trees on the lawn.

Another matter that we would soon have to deal with was that of Professor Pierre Le Roux’s replacement to the chair of Celtic Studies of Rennes University: he had already reached retiring age. There were various potential candidates to succeed him: Roparz Hémon seemed to us to be exactly the right person for this post. None other deserved it as much as he did. I had already discussed this with Jean Mouraille, without even knowing whether Roparz Hémon, whose frequent changes of mood were unpredictable and who was always on bad terms with administration, would agree to submit his candidacy. His appointment was possible as he had passed the Higher Diploma for English, on condition, though, that he first present a thesis he had as yet neglected to submit. We had just placed Roparz Hémon at the head of the Celtic Institute; recently formed it had gathered together a number of Breton personalities and others from the world of arts, letters and culture. I put the matter to him. He must have been having one of his good days as he agreed to let us go ahead with the necessary arrangements: I explained to him that we felt the chair of Celtic Studies of Rennes University should be the crowning achievement to his university career and to the considerable work he had already done so well at the head of Gwalarn. I had no idea at the time that in putting forward his candidature I would come up against the long-standing Breton spelling argument that has divided Breton circles since the beginning of the century, and which I consider to be completely futile.

All those concerned with the fate of the Breton Language had long been aware that we would have to achieve a common Breton spelling, being a requirement for reasonable teaching in the schools. All languages, including the French language, had been through this stage. Efforts in favour of a standard Breton spelling, already well advanced by adopting the K.L.T. at the beginning of the century, had started again before the war and had failed, due to the opposition of Roparz Hémon, supported by Francois Vallée, Meven Mordiern and a few others. But this came to an end in 1941, owing to Roparz Hémon’s change of mind. Had he maybe realised its necessity, coming up against problems that were more practical than theoretical, since taking charge of Radio Rennes-Bretagne? And had his daily contacts with the eminent Celtic authority, professor Weisgerver, played a part in this change of mind? What is certain, is that when Roparz Hémon accepted to work on a standard Breton spelling, this time incorporating that of the Vannes area which had been the last one left out of the reforms made through the adoption of K.L.T., he had in reality come around to an opinion we already held for a long time. The members of the Kuzul Meur unanimously reaffirmed this opinion at some of their meetings held in the presence of Roparz Hémon, in spite of his reluctance to comply with them. Being in charge of Ar Brezhoneg er Skol, I was fully conscious of the necessity for a Standard Spelling , at a time when we were finally starting to make some progress towards the generalised teaching of Breton in the schools. I was neither a philologist nor even a Breton speaker capable of appreciating philological arguments, but simply as a man of action, committed to concrete results, these changes seemed to me to be necessary.

Symbolically maybe, it was in my office of “La Bretagne”, on the 8th July 1941, that the meeting was held when the agreement for the creation of a standard spelling, better known today under the name of ZH, was signed by the main coordinators of Breton publications. I was present with Robert Audic, representing Ar Brezhoneg er Skol and with Xavier de Langlais who had been the initiator of the reform before the war. Loeiz Herrieu represented the writers from Vannes and Yann Vari Perrot, the brothers Uguen and Pierre Mocaër represented the supporters of the K.L.T.

I had relinquished my office to Roparz Hémon who thus presided at the meeting. He detested admitting that he had been wrong, or had made a mistake, or had changed his mind: his character on the whole often made him curt and intolerant. His relationships with people were never very easy and he never fully confided in any one. Thus he preferred to explain that if he had changed his mind since 1938, it was “dre urz” or by order, without specifying who had given the order to which he referred. I remember this very clearly as his statement gave me a start, being so flagrantly inaccurate. Everyone knew this was not the case and that in fact it had been a belated compliance, though maybe reluctant, with an opinion he had not held previously. Unless he was pretending to consider the advice given by the Kuzul Meur as an order. But, having thus left the origin of his compliance rather vague, he left himself open later on to malicious criticisms and comments, as unjust as they were inaccurate, which made out that it was the Germans who had in fact insisted on the Standardised Breton Spelling. Nothing is further from the truth. The Germans did not care less about the Breton Spelling, even though professor Weisgerber may have had a personal opinion on this point. As far as we were concerned we did not care for the ZH more than any other spelling: the main thing was that this spelling be a standard one and that Breton writers had agreed to it.

It had been decided that textbooks, educational and reading books being the ones most urgently needed, should gradually be printed with the new spelling. Breton publications and journals would follow, gradually enabling their readers to become accustomed to the new writing. I therefore obtained permission from the academic authorities that, for the moment, both spellings, the K.L.T. and the Z.H., could be used simultaneously in the schools, according to the textbooks being used and the teachers’ knowledge of one or the other. Although the academic authorities had not given this permission without some reluctance. The Head of Educational Authorities was against it and refused to comply unreservedly with the new standardised spelling. The Comité Consultatif had agreed with my proposal of a compromise suggesting that both spellings could be used in the schools. This decision was put in a favourable manner by the Regional Prefecture to the National Education Department, who accepted it. The Head of Educational Authorities could now no longer oppose it. But this agreement had not been given without an ulterior motive that was soon revealed in the matter of the chair of Celtic Studies.

Pierre Le Roux, a disciple and friend of Francois Vallée, who had tenure of the chair of Celtic Studies in Rennes at the time, was against the spelling reform, and was the one who had notified the Head of Educational Authorities not to comply, particularly as the supporters of the reform had not even asked for his advice. We had certainly been at fault in not having made some attempt to involve him, but had practically forgotten he existed as he was seldom talked about. Engrossed in his scholarly work and the preparation of his Linguistic Atlas, like many specialists of the Breton language, of old Galois or of old Irish, he had nearly forgotten that Breton was a living fabric and not a dead language and should thus not be considered or treated in the same manner. In any case, when I put forward the name of Roparz Hémon to be his successor, I came up against his complete, absolute and final opposition. Naturally, the Head of Educational Authorities was behind him, quite pleased no doubt at these differences of opinion between Breton specialists.

It is possible that Pierre Le Roux already had a candidate to succeed him in Father Francois Falc’hun, though his name was not mentioned at the time. But the latter had come to see me in my office, having probably heard that I supported Roparz Hémon’s candidature for the chair of Celtic studies. He put forward his reasons why he was against the spelling reform, reasons which he assured me were scientific ones, but which I was personally incapable of assessing. He explained his theories to me: what I understood was that he considered spelling should to a certain extent be “fluid”. I understood that he even called into question the K.L.T., and I wondered where we would end up if we were to listen to him! What was needed was a standard spelling to be decided on once and for all: whether it was considered as being a good or a bad one by different people was really of little importance.

It was no surprise to find that the academic authorities in Rennes followed Pierre Le Roux’s advice and had no wish to accept the Z.H. as being, henceforth, the Breton standard spelling. Scientific and other reasons were put forward: it was also said that all those who had written in the K.L.T. since the beginning of the century, might no longer be read by some of their readers and their descendants, if the Breton spelling was altered to that extent: one wonders what Shakespeare or Ronsard would have thought of that argument! Neither was there any willingness to comply, in ecclesiastic circles and among the Private Education authorities in the Finistère, with a reform they criticised. Many thought it was pointless, one of them being Canon Favé, who would replace Yann Vari Perrot on the Comité Consultatif after the cowardly assassination of the latter in December 1943, believing that the compliance of the Vannes writers to the K.L.T. was inevitable sooner or later. Taldir shared their point of view and had also not taken part in the meeting for the Standardisation, no doubt because he was on bad terms with Roparz Hémon, and had insisted on presenting an official report to the Comité Consultatif sharply criticising the reform and rejecting the new spelling.

Now that Roparz Hémon had lent his name to the reform, in spite of his earlier reluctance, he also certainly obstinately refused to budge from this position. It was hopeless to think he could be made to go back on what had been done. His stubbornness was well-known amongst us, and we had all gone to a lot of trouble to make him change his mind the first time. It had only been as a result of the new situation we had brought about that his first position had been influenced. Roparz Hémon was not known for his diplomacy or flexibility. The time spent in persuading, seemed to him a waste of time, whilst the pursuit of his work as a linguist and writer urgently required his attention. Even though all of us were taken up with our own political action, we were undoubtedly still to blame in allowing him to act, or not act, on his own. Certainly, at least, Francois Vallée and Pierre Le Roux should have been more closely associated with our preoccupations and our work, and been more effectively confronted with the problems we had to resolve. But Roparz Hémon would probably also have taken offence at any interference in a field that he considered was exclusively his. As for myself, I thought that the standardisation of Breton spelling was essential: but in reality the structure and details mattered little to me.

The appointment of Pierre Le Roux’s successor to the chair of Celtic Studies was not of any great urgency: Roparz Hémon first had to submit his thesis before his candidacy could be considered. I therefore decided to use delaying tactics, and the Comité Consultatif’s Education commission adopted the same attitude. Rennes University, through the Rector, also did the same, keeping Pierre Le Roux on in office after he had passed retiring age. A solution to this matter of the chair of Celtic Studies was only found after the Libération, by the appointment of Father Francois Falc’hun, an ecclesiastic rather lost in that secular place. He also had his own idea of Breton spelling which was neither the K.L.T., nor the Z.H. He in turn proceeded to create a new Breton spelling that was pompously christened the “University Spelling”, and that his disciples, though still few in number, started to use in their writings, thus invalidating in one go all previous efforts towards spelling standardisation that had been deployed since the beginning of the century! Spurred on by this official example and much to the delight of National Education senior civil servants, others subsequently came along who also had their personal ideas on the subject, which were not those of Father Francois Falc’hun, nor those of Roparz Hémon, nor those of Pierre Le Roux. There was no reason why this should stop!

Meanwhile unfortunately, the Breton language continues every day to lose ground among the people. What do our nit-picking scholars and learned specialists care! : It is much easier to compile learned works, each one claiming to be the definitive one, on dead languages than on living ones that, alive, continue to develop! As for myself, it is since that time when I took a closer interest, purely for practical reasons having no scholastic competence, in the spelling standardisation and in the chair of Celtic Studies that I think Francois 1st, King of France, was right. His Villers-Cotterêts decree on the rules governing the French language was an act of great policy for its future: setting out the spelling of a language is far more the business of a government than that of specialists: if one wants to teach that language and prevent it from degenerating, it is important that it should not be left at the mercy of the intellectual speculators and pointless discussions of the latter; it could possibly be done in the case of the French language, strong and well established, nearly five centuries after the Villiers-Cotterêts decree! But in the case of Breton, a weak and practically dying language, it was unthinkable and suicidal. How is it that our specialist scholars cannot see that their discussions are playing into the hands of the centralised powers and administrations that will always remain hostile to their cause? Is it not the latter’s ultimate goal to eliminate Breton, and other languages still spoken in a France that will only attain perfection in their eyes when these languages have all disappeared? Alas, it is seldom in fact that any specialists are capable of grasping and understanding the overall implications of a problem of which their speciality is but a small part. They are too wrapped up in the latter to be able to recognise the moment when it is necessary to pass over it.

IV

There may not have been any glory to these constant little battles between the Standing Commission of the Comité Consultatif, being the executive body of the Comité, and the State’s centralised administration, but nothing in life can be obtained without effort and conquests. It is by dint of taking small steps that one ends up by taking big steps. Our efforts enabled us to obtain results that were not unimportant on a cultural level. As I write this, the Breton movement today has not as yet succeeded in fully recovering them after the Liberation’s repressive measures, in spite of a broader foundation and the existence of new regional institutions for a few years. On the eve of the Libération, the teaching of Breton History was becoming standardised in primary schools, and also for the exams. A summer school had been created for the training of teachers and professors in Breton. Breton language papers were part of the administration exams in the three Breton speaking departments. An Institute for regional administrative studies had been created at Rennes University. We were, by force of circumstances, moving towards the creation of a body of Breton civil-servants in Brittany and Breton speaking in Basse-Bretagne, which was one of the goals we had put forward. I have no doubt that we would have moved towards new achievements if time had been on our side, and that those we had attained would have become firmly established. The Breton State’s Intermediary Commission had three quarters of a century in front of it to provide practical, administrative, financial and institutional content to the exercising of provincial Autonomy. In front of us, we hardly had as many weeks as they had years.

The Comité Consultatif planned to intervene in other fields apart from the cultural one. The Fine-Arts Commission under the leadership of André Dezzarrois had succeeded in saving the bronze statues of a number of our national heroes from destruction, as for example that of Laënnec in Quimper and Richemont in Vannes. We had succeeded in saving the grave of Chateaubriand and the chapel of La Clarté that were threatened because of being in strategic locations, also the towers and belfries of some other churches and lesser known chapels. We also succeeded in having the Chief town-planner submit his plans for reconstruction and regional development to us. He was not of Breton origin and we were wary of his initiative.

We also obtained agreement that town-planners appointed to Brittany should be aided by a Breton assistant if they were not of Breton origin. Certain sites and buildings that had not been so before, were now protected thanks to a so called “regional” classification system, called for and organised by the Comité Consultatif .

Likewise, the General Affairs Commission, lead by Pierre Mocaër, had in practice become the Social and Economic Affairs Commission. We had successfully intervened on numerous occasions for the protection of the Breton population’s interests in matters of supplies, metals tax, antiaircraft shelters, the easing of traffic and employment services. The behaviour of civil-servants dealing with the public did not escape our vigilance. The Post-Office headquarters had to modify its hostile position as regards the handling of letters with addresses written in Breton. The telephone switchboard operator in Huelgoat who took the liberty of cutting off any telephone conversations in Breton, was transferred, at our request, by the Regional Prefet .

In fact, the Standing Committee and the Comité Consultatif did not hesitate to call the heads of the various services in the region, teachers, departmental inspectors and the head of Economic Affairs, for consultations when necessary. Later on, when the Comité Consultatif’s actions were being judged by the Commissioner of the Republic of the Liberation, Victor Le Gorgeu, in order to condemn it, he wrote that the members of the Comité had the nerve to, “extend their mandate to the economic field. They wanted to be consulted on all matters concerning supplies, the distribution of Breton products, agriculture and fisheries. They had, in fact, made a point of telling the Regional Prefet that they would be examining these problems from the purely Breton aspect.”

It was those very things that we are proud of having done. And when we did them we were always careful to emphasize our position: I was very specific about this, and we always declared, whenever we could, that the line of action we were taking was in defence of Breton interests, with no prejudgements of present or future French governments, nor of the outcome of the present conflict in which we displayed our position of neutrality. This was a world conflict beyond our control, on which we had no intention of taking a standpoint. Our action was in line with the continuity of Brittany, a nation we served, and of the people of Brittany, drawn into a painful situation for which neither of them was responsible and who would survive this new turmoil just as they had survived others.

I was also very specific in my campaigns for our freedom, both in the Comité Consultatif and in my newspapers, to dissociate Maréchal Pétain himself, the head of State, from the mistakes and blunders of his government and his administration and also from the hostility, lack of understanding and resistance we came up against in government and administrative spheres in the course of our struggle. It was against the government and its local representatives that we struggled, not against the person who had taken on the responsibility for the State in order to maintain its unity. I was only carrying on a firmly-rooted tradition in the History of Brittany before the French Revolution. The States and Parliament of Brittany never attacked the king himself during the course of the battles fought by the Breton nation to preserve and increase their autonomy, but it was the excesses and arbitrariness perpetrated in his name by his representatives and ministers that we targeted .

Outside of their involvement with the Comité Consultatif, it’s members were free to follow their preferred choice of politics. We have always maintained this position. It appears particularly in the drafting of “Projet de Statut pour la Bretagne” presented by a unanimous Comité Consultatif, as early as its second plenary session in January 1943 , to the Vichy government through the Regional Prefet . We wanted to point out to him how far we wanted to go in pursuit of provincial autonomy and also to reinforce that what we were requesting from him, we would also request from successors. I had simply taken up, in order to draw up this Projet de Statut, the broad outlines of the one which had already been signed by a number of Breton personalities from all the political, economic, social and cultural circles: but it had to be unanimously presented by the Comité and signed by all its members. This was not a problem for those members of the Comité representing the large Breton associations. But there were still the signatures of those personalities who had been directly appointed by the Regional Prefet. Finally none of these hesitated to sign. The Projet was read by R. de L’Estourbeillon at a plenary session. Though a little surprised by this demonstration of independence, Jean Quenette promised to transmit the document we gave him to the Vichy government: it did not surprise me that we never received a precise answer from the latter! Most of its members abhorred any impulses for regional autonomy as much as their predecessors and their successors did.

The Projet de Statut, of course, called for the creation of a Brittany with five departments and we had not stopped indicating our determination on this point. We already had a representative of Loire Atlantique with us, professor Guéguen from the Pharmacy school of Nantes. Having obtained from the Regional Prefet the option to co-opt certain members, we called on Angot from Nantes to join us. He was the general secretary of the Nantes Canning Factories Union and a well known figure from the Nantes business community, who in the past had fought his first battles with the U.R.B. We also used this ability to assert our independence from those at present in power, German as well as French. We called on Francois du Fretay, the Senator for Finistère, who had just been incarcerated for a few weeks by the Germans. Later, we called on Commander Robert Le Masson, a well known writer from Vannes, who had just scuttled his vessel in Toulon harbour so that it would not fall into the hands of the occupying forces.

There was also the question of having a representative from the P.N.B. on the Comité Consultatif which did not fail to come up. Several unofficial conversations were held on this subject without success. At one of our plenary sessions, Mme. Galbrun, who was herself a member of the P.N.B. and which Jean Quenette was certainly not unaware of, finally asked the question officially. Léon Le Berre again asked the question at a subsequent session. Without giving the members of the Comité the option of discussing the matter, Jean Quenette replied that it did not seem possible, for himself nor for the government he represented, to admit representatives from an essentially political organisation to sit in on an, he reminded us, essentially cultural organisation . He added that he was quite prepared to explain this position to the official representatives of the P.N.B. should he meet them.

A few weeks later, there were unofficial negociations held in Paris between Jean Quenette and Yves Delaporte, which did not come to any clear decision. It was important on a political level that a contact be established: I had already taken advantage of Raymond Deugnier’s presence in the secretarial services of the Rennes prefecture to organise an unofficial friendly meeting at my place between Raymond Delaporte and himself. At the time, there was no question of this meeting being able to lead to anything on a practical level. Francois Ripert , who was then in charge, considered the P.N.B. to be an antagonist not to be spared . But it had always seemed to me useful to make contacts which, at a certain time, could only help along the settlement of the Franco-Breton dispute. Some may be surprised at my attitude: but I have never had, and will certainly never have, a purely Manichean concept of politics and society. Only some sectarian ideologists, detached from reality, or simplistic minds could regard it in that manner. They forget that in politics as in life, compromise and reciprocal relationships are always necessary: without them, problems can only be resolved through the use of force or the Gulag, regardless of the rights of those who do not think in the right way according to the authorities at the time. The essential problem in the governing of men as in that of things is to know when to reconcile opposites and not to exacerbate them. This is the price for equilibrium, which is the very foundation of life.

Jean Quenette, as a politician, was certainly not your average Prefet. His understanding and open-mindedness was not to be found in his successors unfortunately. Whilst he considered his task to be a government assignment, the others were first and foremost career Prefets, who considered the usual administrative routine to be of more importance than the particular problems of the position they held.

His independent spirit had cast a shadow over his relationship with the Feldkommandantur. Pressures from the Germans certainly had something to do with his departure in July 1943. There is also no denying that his Breton politics had aroused strong criticisms amongst the Senior Administration’s traditional administrative circles in Vichy, and the envy of his colleagues’ vis-à-vis this Prefet who had been “brought in from outside” added to these criticisms. When he officially made his farewells to us at the last session of the Comité Consultatif that he presided over, at the Chateau de Josselin on the 15 July 1943, he did not hide from us his bitterness at having to leave an unfinished task behind him.

– “I would have liked to build up a Breton Province,” he told us, “and I felt much more like a Governor than a Regional Prefet.”

For that thought alone and for the achievements he carried out in such a short space of time, his name deserves to appear in our history.